When Justice Depends on Your Address: The Unequal Rollout of Prop 36

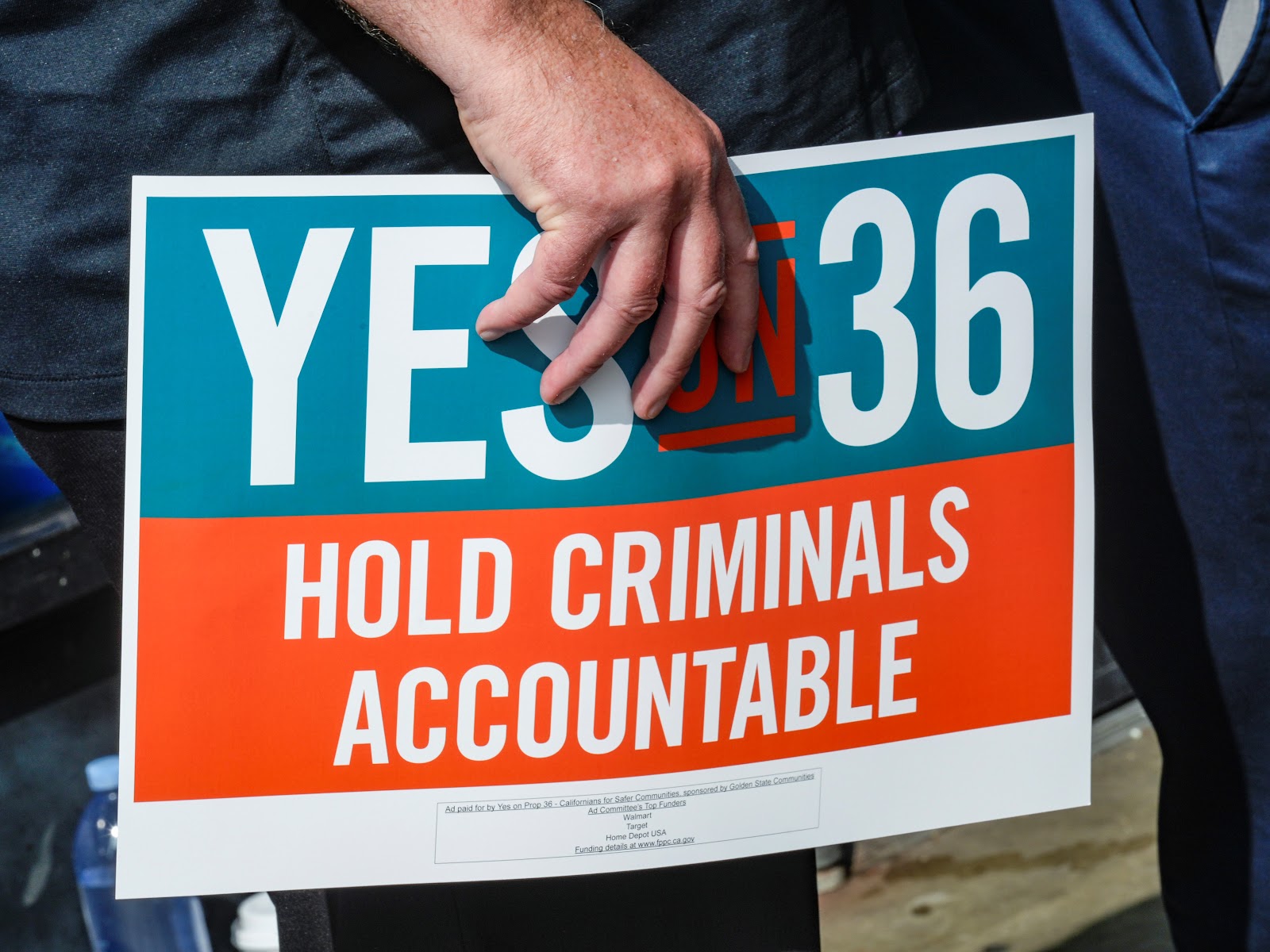

Supporters of Proposition 36 framed it as a path to accountability. Its uneven rollout instead exposes how justice in California remains divided by geography and resources. Photo by Damian Dovarganes.

In California, justice has never been a single system—it’s fifty-eight. Each county enforces its own interpretation of the law, shaped as much by local budgets and political will as by the law itself. When voters approved Proposition 36 in December 2024, many believed the measure would finally stitch coherence into the state’s justice system, promising to restore accountability by making it easier to prosecute repeat offenders, closing loopholes, and bringing consistency to sentencing. For a state long criticized for its uneven enforcement of justice, it seemed to be a step toward making “equal under the law” more than an aspiration. Yet as the measure takes effect, it exposes a deeper paradox: what was designed to unify has instead illuminated the powerful role of local discretion, revealing that California’s justice system remains less a single structure than a mosaic—fragmented, uneven, and defined by where one happens to stand on the map.

Proposition 36—officially titled the Homelessness, Drug Addiction, and Theft Reduction Act—was placed on the ballot in 2024, initiated by a coalition of law-enforcement associations, retail industry groups, and victims’ rights organizations who argued that California’s recent criminal justice reforms had allowed repeat offenders to slip through the cracks [1]. They framed Proposition 36 as a necessary course-correction rather than a full reversal of earlier efforts, pointing to reforms such as Proposition 47 (2014) that had reduced penalties for theft and certain drug-possession crimes. Critics of those measures claimed they weakened deterrence, emboldened serial theft and drug use, and eroded public confidence in the justice system’s fairness and effectiveness [2].

In response, Proposition 36 outlines two major reforms designed to toughen penalties for repeat offenders while expanding access to treatment. First, it reclassifies certain repeat thefts of goods valued under $950—previously misdemeanors under Prop 47—as felonies for individuals with two or more prior theft convictions. This change allows prosecutors to pursue harsher sentences for repeat shoplifters and organized retail theft cases that had previously been charged only as misdemeanors, even when the dollar amount was low [3]. Second, it establishes a new category known as a “treatment-mandated felony” for people repeatedly convicted of drug possession. Under this provision, judges may sentence individuals to court-ordered rehabilitation programs instead of jail, but with felony-level supervision to ensure compliance [4].

While supporters argue that Proposition 36’s balance between accountability and recovery responds to public frustration over rising property crime and visible drug use, its early implementation has instead illuminated what legal scholar Kal Raustiala (2005) called California’s “geography of justice.” In his analysis, Raustiala described how the reach and application of law vary across space, creating a system in which the meaning of justice shifts with jurisdictional boundaries [5]. Nowhere is this concept more vividly realized than in California’s decentralized criminal-justice landscape, where Proposition 36’s rollout has exposed two interrelated problems. First, uneven enforcement across counties that turns justice into a matter of geography, and second, the collision between a more punitive law and a tightening state budget that leaves counties unable to implement it equitably.

Perhaps the clearest sign of Proposition 36’s uneven enforcement across counties is the degree to which prosecutorial discretion determines how the law is applied. Rather than adhering to a shared standard, counties have enforced Proposition 36 through their own philosophies—products of local politics. As the Public Policy Institute of California observes, “Overwhelmingly approved by California voters last November, Proposition 36 … prosecutors have filed thousands of new felony drug and theft charges — and counties vary substantially in using the new approach” [6]. The San Francisco Chronicle similarly reports that “five months after California voters approved harsher punishments for repeat theft and drug crimes, an early snapshot of charging data reveals uneven implementation of the law across the state” [7]. This acknowledgment of “substantial uneven variation” underscores that the statute’s promise of consistency is governed less by uniform policy than by local choice.

In Los Angeles County, District Attorney Nathan Hochman hailed the filing of over a thousand new felony petty-theft and shoplifting cases as evidence that “Proposition 36 is working” [8]. His declaration reveals how discretion can distort legislative purpose: by equating “working” with higher prosecution numbers. If “working” is measured by counts of new felonies, discretion predictably shifts toward charge inflation, greater bargaining leverage, and carceral signaling—metrics that reward spectacle and quantity over equity and eclipse the statute’s rehabilitative aims.

Yet this enforcement logic is not a statewide practice. The P.P.I.C. notes that “about 1,500 theft and 1,900 drug cases have been filed by prosecutors applying the new law’s felony charges,” [9] but the rate of filings “ranges from 24 and 19 in Kern and Orange Counties, respectively, to about 2 in both Fresno and San Francisco” [10]. This twelvefold gap is not credibly explained by crime incidence alone; it reflects different prosecutorial risk tolerances, political incentives, and institutional cultures. In high-filing counties like Kern, prosecutors appear to treat felony charging as a deterrence strategy and a public cue of toughness, prioritizing certainty and severity of punishment. In low-filing counties like San Francisco, discretion is exercised to screen cases more narrowly and preserve diversion capacity, signaling a competing theory of public safety rooted in rehabilitation. The result is a geography of charging where the same conduct triggers different legal realities—not because the statute varies, but because the enforcers do.

Therefore, if prosecutorial discretion determines how Proposition 36 is applied, geography determines what justice ultimately delivers. In other words, the same offense can produce entirely different outcomes depending on where it occurs—a reality scholars describe as “local justice drift.” In one county, a low-level drug offender might receive diversion, probation, or treatment; in another, the same conduct results in a felony conviction, jail time, and a permanent record. These outcome disparities reveal that Proposition 36’s supposedly uniform standard disintegrates when filtered through local politics, institutional capacity, and prosecutorial priorities. As the P.P.I.C. notes, “California has a long history of county-level discretion leading to inequities in sentencing, parole, and law enforcement priorities” [11]. Proposition 36 extends this legacy by ensuring that the consequences of an arrest depend more on geography than on the crime itself.

Even where treatment is written into law, its implementation fractures along the same geographic lines that shape sentencing. The San Francisco Chronicle reports that “in Stanislaus County, which filed the highest number of drug-related cases per capita among California’s 20 most populated counties, Public Defender Jennifer Jennison said no one has been enrolled in treatment,” a reflection not of statutory limits but of how local prosecutors and courts choose to interpret Proposition 36’s rehabilitative mandate [12]. In Stanislaus, the decision to emphasize charging and case-filing over diversion effectively closes off the very pathway the law was designed to create. CalMatters similarly notes that “some counties are planning to fold treatment-mandated felony cases into existing collaborative justice programs, while others plan to create a standalone court,” revealing a landscape where procedural design varies county by county rather than following any statewide standard [13]. These divergences are not merely administrative; they produce fundamentally different legal experiences. In counties that choose to integrate Prop 36 cases into long-standing collaborative courts, defendants encounter a system that frames addiction as something that can be addressed through structured intervention. In places like Stanislaus, where no treatment enrollment occurs at all, the identical offense leads to an entirely different legal pathway. Sacramento Superior Court Judge Lawrence Brown captures this patchwork plainly, noting that drug-addiction evaluations remain an “open question” in many counties because each jurisdiction has charted its own approach [14]. One year into implementation, CalMatters concludes that “few people are finding their way into the treatment [Proposition 36] promised” not because the law changed, but because counties interpret and operationalize it in radically different ways [15]. Under this model, the prospect of rehabilitation is not a universal feature of Proposition 36 but a local choice determined by geography rather than statute.

If Proposition 36’s uneven enforcement reveals how local discretion fractures the meaning of justice, its fiscal impact shows how scarcity determines the limits of what justice counties can even attempt. California entered the measure’s rollout at a moment of statewide austerity, with the Legislative Analyst’s Office warning that “the 2025–26 budget provides $17.3 billion from the General Fund for judicial and criminal justice programs, including support for program operations and capital outlay projects. This is a decrease of $569 million, or 3 percent, below the revised 2024–25 level” [16]. A three-percent cut may seem modest, but its effects are concentrated: fewer public defenders to handle a surge in felony cases, fewer court staff to move those cases through the system, and fewer behavioral-health providers to accept people sentenced under the new treatment-mandated felony category.

In addition to the budget cuts, state analysts were explicit that the law would not be fiscally neutral. The Legislative Analyst’s Office cautioned that “Proposition 36 makes some misdemeanors felonies and could increase state and local corrections costs under certain scenarios,” and projected that “Proposition 36 will cause the average daily prison population to be about 570 higher (or 1 percent) in 2024-25 and 3,300 higher (or 4 percent) in 2025-26” [17]. The California Budget & Policy Center sharpened the warning, estimating that “Prop 36 is estimated to cost the state anywhere from several tens of millions of dollars to the low hundreds of millions annually” [18]. Taken together, these numbers describe a deliberate policy choice: to expand felony exposure and grow prison populations at the exact moment when the state is cutting the overall justice budget. That mismatch does not just strain institutions; it forces them into triage. Counties are no longer deciding whether Proposition 36 is good policy in the abstract. They are deciding which parts of it they can afford to honor and which will quietly be sacrificed to keep the system functioning at all.

This fiscal triage has profound consequences for the law’s rehabilitative intentions because Prop 36 presumes a treatment system that is already buckling under unmet need. Counties cannot fabricate clinical staff, residential beds, or case-management infrastructures simply because the statute demands them, which is why The Guardian’s warning lands so forcefully: “We do not have enough treatment for the people who want it, let alone the people we are trying to force into it. Counties across California are already struggling with shortages of services and residential beds, with a survey finding that unhoused people interested in addiction treatment regularly can’t get a spot” [19]. That line exposes the core contradiction of the law. If people who actively seek care cannot secure it, the idea that the state can now mandate treatment at scale is structurally impossible. The early rollout confirms this tension between legal aspiration and material capacity: when the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office concedes that “early results show Prop 36 struggling with ‘mass treatment’ pledges for homeless drug offenders,” it is effectively acknowledging that the treatment arm is collapsing at precisely the point where the law claims to be most transformative [20]. The population that the statute targets most aggressively—unhoused people with substance-use disorders—is also the group that is hardest to serve in a resource-starved environment, so the gap between what Prop 36 promises and what counties can fund becomes widest exactly where the law insists on “mass treatment.”

The problem, then, is not a few service gaps but a structural capacity deficit that determines how Prop 36 functions on the ground. Sacramento County’s behavioral-health director states the core reality bluntly: counties “simply don’t have enough capacity right now to take on a whole new population of folks that are getting mandated into treatment” [21]. A treatment system that cannot meet existing voluntary demand will not be able to absorb a legally compelled caseload, and that deficit becomes visible immediately in jail populations. In Los Angeles County, researchers found that “on average, 35 people per week enter county jail on Prop. 36-related charges as the most serious offense,” a weekly surge that exposes how little excess capacity counties have [22]. The same report warns that “if the impact of Proposition 36 continues in this way, County jail will return to overcrowding and prevent the closure of [Men’s Central Jail],” reversing long-standing decarceration plans [23]. Faced with this pressure, counties fall back on the only system they already have the staff, space, and funding to run—jail. As Oakland Voices observes, “Prop 36 is only increasing criminalization of people who struggle with poverty, substance use, or both,” because the supports required for treatment-mandated felonies— counselors, psychiatric care, transportation assistance, court liaisons, long-term case management—are precisely the supports counties chronically lack [24]. People with unstable housing, untreated illness, or unreliable transportation become the first to be labeled “non-compliant,” not because they reject treatment, but because they cannot meet the logistical demands of a program that does not have enough staff or slots to accommodate them. Under conditions of austerity, counties do not default to punishment because rehabilitation has lost legitimacy; they default to punishment because people with the fewest resources are the easiest to absorb into custody when the treatment side of the system cannot carry them.

Proposition 36’s rollout shows that California’s justice system fractures along two intertwined fault lines: the discretionary power of counties to enforce the statute differently and the fiscal capacity of those counties to carry out what the law demands. In the first half of its implementation story, geography determines outcomes as prosecutors in some counties aggressively file new felony charges while others narrowly screen cases, producing a landscape where the same conduct triggers entirely different legal consequences depending on the jurisdiction. The second half reveals an equally consequential divide shaped by resources, not philosophy. Counties with stronger fiscal reserves can approximate the law’s rehabilitative intent, while those operating under austerity default to punishment because they lack the public defenders, treatment beds, behavioral-health staff, and court capacity required to offer real alternatives. These dual disparities, one rooted in local enforcement culture and the other in resource scarcity, ensure that Proposition 36’s promise of accountability and rehabilitation dissolves into a system where justice is rationed by place and by budget. If California intends to make justice truly uniform, it must both standardize enforcement practices across counties and invest in the treatment infrastructure, behavioral-health workforce, and defender systems that make equitable implementation possible. Without confronting these twin inequities, Proposition 36 will remain less a reform than a diagnostic, revealing exactly where and why justice still depends on one’s address.

Sources

[1] California Legislative Analyst’s Office. “Proposition 36: Allows Felony Charges and Increases Sentences for Certain Drug and Theft Crimes. Initiative Statute.” September 10th, 2024. https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Detail/4921

[2] California Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 36.”

[3] California Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 36.”

[4] California Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 36.”

[5] Raustiala, Kal. “The Geography of Justice.” Fordham Law Review 73, no. 6 (2005): 2501–2573. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4083&context=flr.

[6] Lofstrom, Magnus, and Brandon Martin. “Early Implementation of Prop 36 Varies Widely across Counties.” Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) Blog. April 23rd, 2024. https://www.ppic.org/blog/early-implementation-of-prop-36-varies-widely-across-counties/.

[7] Angst, Maggie, David Hernandez, and Sophia Bollag. “California Increased Penalties for Some Drug and Theft Crimes: Here’s How the Law Is Working.” San Francisco Chronicle, April 10th, 2025. https://www.sfchronicle.com/california/article/prop-36-crime-20263074.php

[8] Sharp, Julie. “West Los Angeles Alleged Petty Thief Faces Felony Charges under New Prop 36 Laws.” CBS News Los Angeles, May 14th, 2025. https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/west-los-angeles-alleged-petty-thief-felony-charges-prop-36/.

[9] Lofstrom and Martin, “Early Implementation of Prop 36.”

[10] Lofstrom and Martin, “Early Implementation of Prop 36.”

[11] Lofstrom and Martin, “Early Implementation of Prop 36.”

[12] Angst, Hernandez, and Bollag, “California Increased Penalties.”

[13] Mihalovich, Cayla. “People Are Getting Arrested under California’s New Tough-on-Crime Law. Some Counties Aren’t Ready.” CalMatters, February 11th, 2025. https://calmatters.org/justice/2025/02/prop-36-arrests-treatment/.

[14] Mihalovich, “People Are Getting Arrested…”

[15] Mihalovich, Cayla. “California’s Prop. 36 Promised ‘Mass Treatment’ for Defendants. A New Study Shows How It’s Going.” CalMatters, October 13th, 2025. https://calmatters.org/justice/2025/10/proposition-36-treatment-study/

[16] Legislative Analyst’s Office. The 2025–26 California Spending Plan: Judiciary and Criminal Justice. LAO Budget and Policy Post, October 24th, 2025. https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/5085.

[17] Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2025–26 California Spending Plan: Judiciary and Criminal Justice.

[18] Davalos, Monica, and Scott Graves. “Understanding Proposition 36: Why Prop. 36 Fails Californians—Escalating Costs, Deepening Disparities, and Ineffective Solutions.” California Budget & Policy Center, August 2024. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/understanding-proposition-36/

[19] Levin, Sam. “California Police Launch Stings and Arrests under New Tough-on-Crime Measure.” The Guardian, January 8th, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/08/california-prop-36-shoplifting-drug-arrests

[20] “Mercury News: Early Results Show Prop 36 Struggling with ‘Mass Treatment’ Pledge for Homeless Drug Offenders.” Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office, Justice Daily News summary. August 18th, 2025

https://da.santaclaracounty.gov/mercury-news-early-results-show-prop-36-struggling-mass-treatment-pledge-homeless-drug-offenders

[21] Mihalovich, Cayla. “California ballot measure promises ‘mass treatment’ for drug crimes. Can counties provide it?” CalMatters, October 16th, 2024. https://calmatters.org/justice/2024/10/prop-36-mass-treatment/

[22] Garrova, Robert. “LA County’s Jail Population Is Rising. Prop 36 Is Partly to Blame.” LAist. May 2nd, 2025. https://laist.com/news/criminal-justice/la-county-jail-population-rising-prop-36

[23] Garrova, “LA County’s Jail Population Is Rising.”

[24] Woods, Brendan, and Yoel Haile. “Opinion: Why Prop 36 Has Already Failed.” Oakland Voices, April 28th, 2025. https://oaklandvoices.us/2025/04/28/prop-36-increasing-mass-incarceration-systemic-racism/