The Likeability Penalty: How Does Gender Affect Campaign Strategy?

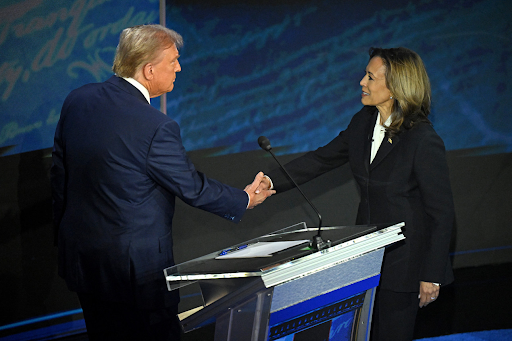

As she walks onto the stage, he makes his way behind the podium. She walks toward him, out of her way, extending a hand. An act of goodwill, compassion, and respect. America watches, forming critical perceptions about her character.

In the past eight years, the United States has seen two female candidates secure a major party nomination for President. While the polls predicted victories for both, voters ultimately did not elect them. The likeability penalty is the idea that assertive traits are negatively perceived towards women, and positively perceived towards men [1]. When female candidates run for office, the way they speak and behave often visibly contrasts with the opposing male candidate. Raising one’s voice or displaying arrogance in any capacity will be perceived as pushy and brusque rather than leaderly and confident, which affects campaign strategy.

This distinction is better described as positive and negative campaigning. When political candidates engage in positive campaigning, they often focus on themselves as individuals. For example, candidates describe their policy plans, vision for the country, qualifications, and accomplishments in office [2]. Negative campaigning, on the other hand, focuses on creating a disapproving perception of the opposing candidate. This strategy can include emphasizing the individual's shortcomings with the intent of diminishing their credibility and reputation. Male candidates have been found to engage more in the latter. However, female candidates typically opt for the former, focusing on positive campaigning and using negative campaign messages carefully. Consequently, male and female candidates’ priorities seem to be flipped.

The 2024 Election: Harris vs. Trump

Positive and negative campaign strategies were distinctly visible during the 2024 presidential election. Kamala Harris’ campaign website offered over eighty pages of policy focusing on Harris’ plan to build an opportunity economy for America’s working and middle classes. Within a mere five pages of the “policy book,” she details visions for expanding child tax credits, investing in food supply chains to lower grocery prices, and passing a federal ban on price gouging [3]. Her campaign website contains more plans, ranging from alleviating the impacts of climate change to reforming our healthcare system [4].

Donald Trump’s campaign website offered a sixteen-page GOP platform and twenty core promises, including carrying out the largest deportation operation the United States has seen, ending inflation, and large tax cuts for workers [5]. The GOP platform begins with a five-page preamble equating common sense to a vote for President Trump [6]. As for its policy proposals, language in the plan states that Republicans would slash wasteful government spending, end global chaos, and reverse harmful Democratic policies. The platform states that the only thing holding American workers back is the suffocating policies of Democrats, drawing a clear line between Republicans and their opposition.

In an increasingly digital age, how candidates speak to voters and what they say can be key to building positive public perceptions. The language used in Harris and Trump’s plans differs starkly.

In Trump's policy plan, negative comments are directed toward Democrats in general, the Biden administration, and Biden himself. The language is forceful and aggressive, describing Democrats as agents of political decline who crush, weaponize, and destroy aspects of the government and society. Contrastingly, Harris did not direct negative comments toward all Republicans. Instead, she focused on creating a divide between Trump’s plan and hers. She also used other entities to discredit her opponent rather than personally doing so. For example, her plan states that the Tax Foundation found that “Trump’s Tariffs” would increase costs for Americans [7]. Harris’ wording is less aggressive, drawing on and citing external sources to discuss the quantitative implications of Trump’s policies.

The end of her plan involves a long citation list, demonstrating her proactiveness in supporting her claims with evidence. This part is missing in Trump’s GOP platform, emphasizing that the approach these candidates took to building credibility while discussing their plan diverged significantly. Harris relied on experts, external organizations, economists, and researchers to validate her claims. Trump did not.

The Harris campaign also sought to divide the candidates morally, reiterating her role as a prosecutor alongside Trump’s felony convictions, asking voters to decide between a candidate who enforces laws and a candidate who breaks them. The image the Harris campaign created is a tale as old as time: good over evil and justice over injustice. Despite this seemingly strong narrative, voters who had tougher stances on crime and policing chose to elect a convicted felon.

In 2016, the F.B.I. investigated Hillary Clinton for her use of a private email server and found no reason to support bringing criminal charges against her [8]. Despite a lack of criminal charges against her, Clinton was branded as a criminal by many. Voters chanted “lock her up,” referring to Clinton, at speeches held four days prior to the election [9]. Trump’s felony convictions and the rhetoric labeling him as a criminal, although dissimilar to the events of 2016 in many ways, are reminiscent of the anti-Clinton backlash during the 2016 election.

In 2016, an investigation alone convinced some voters to cast their ballot for Trump. Surprisingly, felony convictions did not have the same effect against Trump in 2024.

This distinction could partially be attributed to right-wing voters distrusting the media. But why were swing state voters who previously voted blue more convinced by Trump than Harris?

Returning to the likeability penalty, assertiveness and its intersection with the perception of confidence varies between men and women. Bold and loud statements that do not necessarily have evidence to support them are typically received more positively by the public if the language comes from a man rather than a woman. This disparity creates a dilemma for female candidates in navigating the risk of coming off as masculine by being unapologetically decisive. This campaign strategy, referred to as “running as a man,” can create dissonance in voters' minds due to its divergence from traditional gender stereotypes [10]. On the other hand, showing compassion and warmth can result in candidates being perceived as weak. Both outcomes can diminish likability and support.

Creating an image that is strong yet benevolent is not an easy feat.

History Also Plays a Role…

Voters view women as more competent on issues of education and healthcare, while men are viewed as stronger on issues regarding the military and the economy [11]. This is unsurprising. Until 2013, women were banned from combat and prohibited from serving in artillery, infantry, and armor roles. Until 1971, married women were not allowed to serve in the U.S. Foreign Service, preventing them from working in international diplomacy [12]. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act was passed in 1974, allowing women to apply for a credit card and take out a loan without a male co-signer for the first time [13]. Women working in diplomacy and defense and having economic independence are ideas that have gained traction within the past few decades. However, biases persist, especially in fields that have historically excluded women, often leading voters to turn to men during times of war and when the economy is weaker [14].

This reality suggests that female candidates have to work harder to prove themselves as capable leaders on issues that they are generally perceived to be less convincing on. The Harris campaign intentionally put out over eighty pages worth of economic policy and continually highlighted Trump’s affiliation with foreign dictators to weaken his stance on national security–two issues on which he polled higher than Harris.

Comparison Study: The 2020 Election

Both Biden and Trump had low approval ratings before the 2020 election, with Biden polling around 46 percent and Trump polling around 41 percent [15]. An unofficial campaign emerged during this time: the “Settle for Biden” slogan on social media. Its aim was to rally progressives who were disappointed with Biden’s centrism around his candidacy [16]. The campaign focused on portraying Biden as normal compared to Trump and “good enough” to serve as president for the next few years. This strategy was a prime example of negative campaigning, as those who ran the campaign portrayed Trump as dangerous and unfit compared to Biden rather than focusing on what made Biden a strong candidate.

Turning to the 2020 presidential debate, Biden’s rhetoric was also visibly more aggressive than Harris’. During the debate, Biden asked the moderator if he was going to shut Trump up, asked Trump to be quiet for a minute, and called Trump a liar [17]. The reality is that neither candidate was respectful to the other and both candidates frequently interrupted one another, choosing to name-call and mock their opposition's track record rather than define themselves to the American people.

Concluding Thoughts

In the United States, the presence of a woman in a presidential race does not guarantee a victory for an opposing male candidate, but gender does affect campaigning. Female candidates often face unique struggles in convincing voters that they could fill a role that has historically been confined to men. Ultimately, exit polling in 2024 showed that the economy was one of the top issues that influenced voter decisions [18]. But the question remains as to whether a male Democratic candidate would have been in a better position than Harris with voters or if this is solely a partisan issue that does not intersect with gender at all.

The Harris and Trump campaigns differed in both voter perceptions and the way the candidates approached their strategies, but these differences do not indicate that the United States is far off from having a Madam President in the White House. Progress has been made. Female governors, representatives, and senators have been elected to office time and again. Remarkable women have led the U.S. in times of crisis and throughout generations, leaving the title of Commander-in-Chief as solely another proverbial glass ceiling waiting to be shattered.

Sources

[1] The Clayman Institute for Gender Research. “Women Leaders: does likeability really matter?” Stanford University. June 24th, 2024.

https://gender.stanford.edu/news/women-leaders-does-likeability-really-matter.

[2] Hilde Coffé, Theodora Helimäki, & Åsa von Schoultz. “How Gender Affects Negative and Positive Campaigning.” Journal of Women, Politics, and Policy 44, no. 3 (March 10th, 2024).

https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2023.2180610.

[3] Harris-Walz Campaign. “A Plan to Lower Costs and Create an Opportunity Economy.”

https://kamalaharris.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Policy-Book-Economic-Opportunity.pdf.

[4] Harris-Walz Campaign. “A New Way Forward - Website Issues Page.”

https://kamalaharris.com/issues/.

[5] Trump-Vance Campaign. “President Trump’s 20 CORE PROMISES TO MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN! - Website Platform Page.”

https://www.donaldjtrump.com/platform.

[6] Trump-Vance Campaign. “2024 GOP PLATFORM MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!”

https://rncplatform.donaldjtrump.com/.

[7] Harris-Walz Campaign, “A Plan to Lower Costs.”

[8] “Statement by FBI Director James B. Comey on the Investigation of Secretary Hillary Clinton’s Use of a Personal E-Mail System.” F.B.I. July 5th, 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/statement-by-fbi-director-james-b-comey-on-the-investigation-of-secretary-hillary-clinton2019s-use-of-a-personal-e-mail-system.

[9] Timm, Jane C. “Fact Check: Trump Presses Forward With Inaccurate “Criminal” Claims.” NBC News. November 5th, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2016-election-day/fact-check-trump-presses-forward-inaccurate-criminal-claims-n678311.

[10] Dittmar, Kelly. “Gendered Aspects of Political Persuasion in Campaigns.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion, 295–320. Oxford: Oxford University Press, June 13th, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190860806.013.37.

[11] Sarah F. Anzia & Rachel Bernhard. “Gender Stereotyping and the Electoral Success of Women Candidates: New Evidence from Local Elections in the United States.” University of California, Berkeley. June 2021.

https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Anzia_Bernhard_June2021.pdf.

[12] Sullivan, Maggie. “Gaps in Our National Security: How the Lack of Female Leadership Impacts Our Nation’s Success and Safety.” Cleveland State Law Review 72, no. 3. April 24th, 2024.

https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4268&context=clevstlrev.

[13] Gariepy, Laura. “Women and Credit: A Look at the History.” U.S. News. March 24th, 2024.

https://money.usnews.com/credit-cards/articles/women-and-credit-a-look-at-the-history.

[14] “Economic Uncertainty Costs Women Politicians.” Northwestern Magazine. 2019.

https://magazine.northwestern.edu/discovery/economic-uncertainty-costs-women-politicians/.

[15] “Trump, Biden Favorable Ratings Both Below 50%.” Gallup. September 18th, 2020. https://news.gallup.com/poll/320411/trump-biden-favorable-ratings-below.aspx.

[16] Arnold-Murray, Katherine. “Settle for Biden: The scalar production of a normative presidential candidate on Instagram.” Language in Society 53, no. 4. April 30th, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404524000356.

[17] “CPD: September 29, 2020 Debate Transcript.” The Commission on Presidential Debates. September 19th, 2020. https://www.debates.org/voter-education/debate-transcripts/september-29-2020-debate-transcript.

[18] Stephanie Perry & Patrick J. Egan. “NBC News Exit Poll: Voters Express Deep Concern about America’s Democracy and Economy.” NBC News. November 5th, 2024. www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/nbc-news-exit-poll-voters-express-concern-democracy-economy-rcna178602.