The False Promise of American Hypersonic Weapons

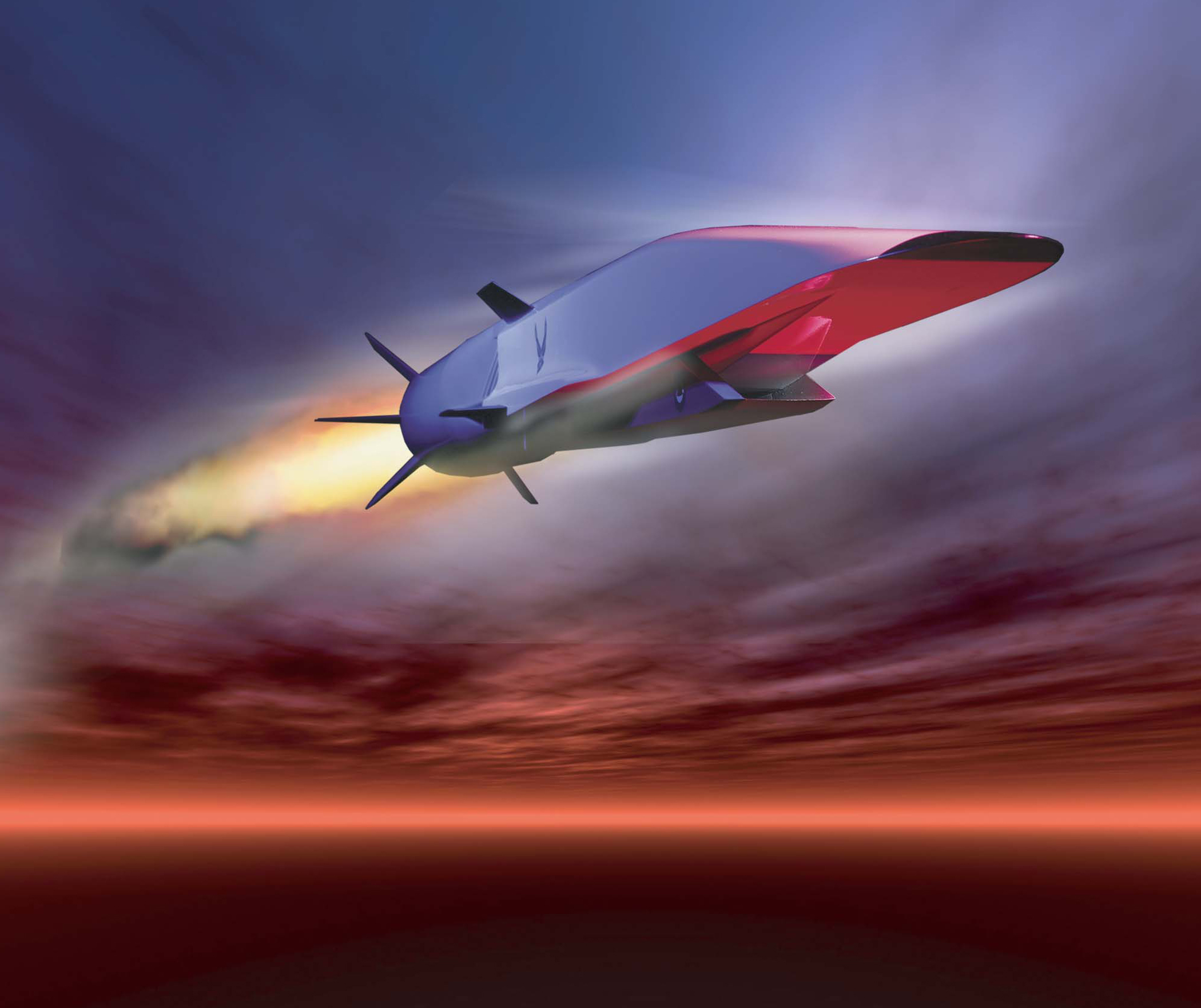

In the early 2000s, the U.S. military under the Bush Administration proposed the development of a weapons system that could deliver a conventional precision strike anywhere in the world in under one hour, a capability that came to be referred to as Prompt Global Strike (PGS). [1] While multiple systems capable of filling this role were considered, one specific technological initiative stood out as particularly promising. The Falcon Project, a cooperative effort between the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the U.S. Air Force attempted to produce a weapon system that seemed ideal for a PGS role: a hypersonic vehicle. [2] In 2010 and 2011, the first successful hypersonic weapons tests were conducted under the Obama administration. [3; 4]

This achievement did not go unnoticed by the rest of the world. In 2014, China successfully tested its first hypersonic glide vehicle, the Wu-14. Four years later, Russia’s newly unveiled hypersonic Avangard missile entered production. It has now been over a decade since the first successful U.S. tests of a hypersonic vehicle, and in that time the U.S. has been surpassed by its peer competitors as its technological progress on hypersonic weapons has stagnated. Amid recent foreign achievements in hypersonic technology such as China’s 2021 missile tests and the announcement of official contracts for Russia’s hypersonic cruise missile, the Zircon, in 2022, many influential voices in Washington are arguing that the U.S. ought to reinvigorate the PGS program and develop a robust American hypersonic weapons system, lest we fall even further behind in the newly emerging hypersonic arms race. [5]

The objective of this article will be to rebut arguments of this sort, in part by demonstrating the substantial costs, both strategic and financial, attached to an American hypersonic weapons program, and in part through an assessment of the threat posed by foreign hypersonic capabilities, alongside an explanation of why hypersonic capabilities of our own would be ineffective in mitigating that threat. Although the Congressional Budget Office has thus far approved proposals to develop and integrate only a conventional hypersonic weapons system into the U.S. arsenal, this article will present an analysis of both conventional and nuclear hypersonic capabilities. [6]

However, before considering the merits of hypersonic development, it is important to address the following questions: what are hypersonic weapons and why are they such a revolutionary technology? We can best answer these questions by contrasting hypersonic missiles with their more traditional counterpart - ballistic missiles. For decades, missiles designed to hit overseas targets in a relatively limited window of time have possessed ballistic trajectories, meaning they spend the vast majority of their flight time in the outer atmosphere traveling on a predictable path before eventually reentering Earth’s atmosphere, where they slow substantially. [1] In contrast, a hypersonic vehicle travels in the atmosphere on a sporadic and unpredictable trajectory at speeds exceeding Mach 5, minimizing air resistance by either gliding or compressing incoming airflow with scramjet engines. [5] This irregular low-altitude trajectory ensures that when compared to ballistic missiles, hypersonic weapons have far less distance to cover, are considerably more difficult to detect, and, crucially, are much faster during the final stages of flight. [7]

This heightened speed and maneuverability during the final stages of a hypersonic missile’s flight lie at the core of hypersonic weapons’ strategic significance. These weapons can, in theory, strike any target imaginable, as their evasive nature allows them to bypass virtually any missile defense system on the planet. For the U.S., a country that prides itself on its overwhelming superiority in ballistic missile defense (BMD) technology, this is a very worrying prospect. [8]

Implications for Nuclear Strategic Stability

At its core, U.S. nuclear strategy can be reduced to two primary objectives. The first and most obvious is the preservation of a credible nuclear deterrent and maintenance of second-strike stability. In other words, if another country were to launch a nuclear strike on the U.S., the U.S. would like to possess the ability to respond in kind, ensuring mutually assured destruction. [9] Secondly, a nuclear arsenal can be used actively, and sometimes even coercively, as a tool for conducting foreign policy. After all, the fact that nuclear powers consistently attempt to increase the size and sophistication of their arsenals, despite the fact that a limited number of weapons of mass destruction should be sufficient to deter a rational adversary, indicates that decisions in nuclear strategy are often guided by something more than a desire for mutual deterrence. Superiority-brinkmanship synthesis theory suggests that a country with a larger arsenal, especially one with advanced missile defense capabilities, will fare considerably better than an adversary with a more limited arsenal in a nuclear exchange. [10] Therefore, even if a country like the U.S. had no desire to engage in an actual nuclear conflict, the possession of an advantage of this sort is exceptionally useful in crisis bargaining and brinkmanship (the practice of making threats and edging closer to conflict with the aim of extracting concessions from an adversary). Theoretically, U.S. nuclear superiority should decrease the credibility of available nuclear threats an adversary can make and increase the credibility of threats available to the U.S. and its allies.

The existence of foreign hypersonic weapons jeopardizes both of these objectives in two key ways. First, the potential for hypersonic weapons to enable counterforce strikes (a nuclear attack designed to destroy an adversary’s nuclear arsenal) is enormously destabilizing. Hypersonic weapons can neutralize BMD capabilities and clear the way for a large number of ballistic missiles or additional hypersonic weapons to neutralize large portions of the U.S. arsenal before the U.S. can retaliate. For this reason, hypersonic weapons create an incentive for countries that possess them to act preemptively, thereby encouraging nuclear first use. [11] Second, hypersonic weapons in the hands of adversaries drastically limit the strategic superiority the U.S. currently enjoys among nuclear powers. This strategic superiority is undergirded by superiority in BMD technology that insulates the U.S. from the most severe consequences of an enemy strike, but if this technology were to be neutralized by foreign hypersonic weapons, then the U.S. would no longer possess a meaningful advantage in crisis bargaining.

While the existence of hypersonic weapons certainly poses a challenge for U.S. nuclear strategy, the presence of hypersonic weapons in the hands of the U.S. would do very little to address this challenge. In the context of stable nuclear deterrence, hypersonic weapons would not increase the credibility of the U.S. nuclear deterrent, as they merely increase the potency of first-strike capabilities that the U.S. has no interest in possessing. The only meaningful role hypersonic weapons could play in increasing strategic stability is as an answer to foreign missile defense technology. If an adversary’s BMD could potentially neutralize any given country’s ability to launch a successful retaliatory nuclear strike, then the costs of nuclear first use for that adversary would be drastically reduced, thereby incentivizing a first strike. While this particular strategic capability is an excellent motivation for other nuclear powers to develop hypersonic weapons, given the potential threat posed by American superiority in BMD, the fact that no U.S. adversary possesses meaningfully effective or threatening BMD capabilities means that hypersonic weapons in American hands would do little to meaningfully contribute to stable deterrence.

American hypersonic weapons would also have a similarly marginal effect on crisis bargaining. Superiority in first-strike capabilities is ineffective in brinkmanship for the same reason it is destabilizing. In a crisis bargaining situation, if an adversary knows that the U.S. has an advantage in a nuclear exchange if and only if the U.S. acts first and initiates conflict, that adversary has an incentive not to back down and make concessions, but rather to act first and initiate conflict before the U.S. can act. [12] This dynamic is often referred to as a “use it or lose it” dilemma. Furthermore, given the lack of meaningful foreign BMD capabilities, U.S. possession of a technology designed to neutralize the advantages in crisis bargaining held by nations that possess advanced BMD capabilities would accomplish very little.

Implications for Conventional Conflicts

The threat posed to the U.S. by foreign conventional hypersonic weapons is far less severe than that of their nuclear counterparts. Nonetheless, many voices in Washington have identified certain niche strategic concerns, such as the vulnerability of American warships to hypersonic weapons that cannot be feasibly intercepted. [12] However, this vulnerability is likely inevitable. Many U.S. adversaries already possess anti-access and area denial capabilities (A2/AD) that can accomplish similar feats, such as loitering munitions, traditional surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and traditional anti-ship missiles. It has been well established that these capabilities have rendered the approach of sending a carrier battle group (a fleet of an aircraft carrier and several warships) into well-defended enemy waters a strategic relic.

The potential benefits of conventional hypersonic weapons development by the U.S. revolve primarily around neutralizing these same adversarial A2/AD capabilities, especially in the South China Sea. For instance, in the event of military escalation over Taiwan, hypersonic missiles could potentially be used to neutralize on-shore Chinese missile batteries within a very small window of time, clearing the way for carrier battle groups that could provide air support for the island. [13; 14] While the Congressional Budget Office has identified this and similar scenarios as sufficiently strategically significant to justify substantial funding for hypersonic weapons development, there are also several problems with developing hypersonic capabilities for this purpose.

First, although hypersonic weapons could certainly destroy an adversary's SAMs or other A2/AD capabilities more quickly than existing technology realistically could, it's unclear how significant that slightly compressed window of time would be. It is plausible that existing cruise missiles or stealthy fifth-generation aircraft like the F-35 could accomplish the vast majority of American objectives in a scenario such as a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, especially given the fact that these weapons could be fired from overseas bases and carrier battle groups stationed in relatively close proximity to the conflict. [12]

Second, it is unclear to what extent hypersonic weapons would be capable of neutralizing A2/AD on battlefields in the near future. Hardened anti-ship missiles are only one piece of the complex patchwork of weapons systems that comprise A2/AD in many strategically significant regions. [15] It is easy to imagine the extent to which a limited hypersonic arsenal might be embarrassingly ineffective in the face of naval mines, offensive cyber weapons, drone-based loitering munitions, or even simply a very large quantity of expendable missile batteries, as weapons systems of these sorts are exceptionally resilient to missile strikes, especially when the missiles in question are as scarce and expensive as hypersonic weapons.

Third, even if U.S. hypersonic capabilities were able to neutralize large swaths of an adversary's A2/AD in a contested region, many of the strategies the U.S. could pursue by doing so are dubious. Despite their potential theoretical effectiveness, nearly all military operations enabled by the presence of American hypersonic weapons in the South China Sea would contribute to a broader strategy that would likely entail either formally or functionally declaring war against a nuclear-armed great power. Admittedly, this argument does beg the question of a much larger debate regarding U.S. foreign policy towards China, but in the context of applications of hypersonics to Taiwan specifically, it is at least worth considering an investment in far less escalatory strategies, such as efforts to make the island a hardened target with robust A2/AD capabilities of its own, before spending the immense monetary resources required for further development of hypersonic capabilities. [16]

In addition to possessing a deeply flawed strategic justification for its existence, an American hypersonic weapon program may be actively harmful for several reasons. First, the development of such a program would be egregiously expensive. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the procurement costs of 300 hypersonic missiles over the next 20 years would reach roughly 17.9 billion dollars. This price exceeds the procurement costs of 300 comparable, highly maneuverable ICBMS equipped with countermeasures designed to facilitate infiltration of an adversary’s A2/AD capabilities by over 4.5 billion. Moreover, 17.9 billion is just the procurement cost for a technology for which an operational variant does not yet exist in the U.S. The challenge of shielding internal circuits from high outside temperatures is one of the most fundamental technical problems involved in the creation of hypersonic weapons. Despite the fact that since 2019 the Department of Defense has poured over 8 billion dollars into research and development of hypersonic capabilities, this problem has yet to be solved. [17]

Second, conventional hypersonic weapons pose a problem of warhead ambiguity. If the U.S. were to launch a hypersonic weapon, even if it was armed with a conventional warhead, other countries would have no way of knowing that was the case. [7] For example, the U.S. does not officially know whether or not Russian and Chinese hypersonic weapons carry nuclear payloads, but because of the strategic importance those weapons would have on nuclear stability if they did in fact carry nuclear warheads, we are forced to assume the worst and prepare accordingly. If these roles were reversed, it seems safe to assume that Russia and China would engage in a similar calculation when faced with American hypersonic weapons.

A similar problem with ICBMs has been fairly well documented. Substantial concerns were raised by prominent members of the defense community over the possibility of using modified ICBMs as a PGS capability because of ambiguity caused by the possession of nuclear and non-nuclear variants of the same missile. [18] While the problem posed by hypersonic warhead ambiguity is similar to the ICBM dilemma in many respects, it may also be even more severe. The speed and unpredictable flight patterns of hypersonic missiles would leave foreign leaders a smaller window of time to make decisions regarding whether to retaliate against what may be an incoming strike, resulting in a reduced ability to make informed judgments regarding the status of a missile as conventional or nuclear. [19, 11] Furthermore, if the primary targets for conventional hypersonic weapons are A2/AD in hostile regions, the true target of a conventional hypersonic strike will likely be almost indistinguishable from likely targets of a hypothetical nuclear strike, giving adversaries even more reason to assume the worst and accidentally begin a nuclear exchange. [12] This particular source of ambiguity is exacerbated by the fact that China often uses the same command and control facilities to direct both conventional capabilities comprising A2/AD and nuclear silos, so a hypersonic strike on such a facility could easily be interpreted as a preemptive counterforce strike. [20]

Third and finally, foreign hypersonic acquisition will inevitably be, to some extent, reactionary to American acquisition. After all, the development of the PGS program under the Bush and Obama administrations has been explicitly cited as a major contributing factor in Russia and China’s decisions to accelerate the development of their own hypersonic capabilities. [21] Every increase in the development of hypersonic capabilities by the U.S. could exacerbate every strategic vulnerability posed to the U.S. by foreign hypersonic development. This consideration is especially important in view of the fact that as the number of an adversary's hypersonic weapons increases, so does its ability to execute a successful nuclear counterforce strike. An increased quantity of hypersonic weapons directly represents an increase in the portion of the U.S. nuclear arsenal that could be successfully neutralized in a counterforce strike. [11]

Steps for the Future

Ultimately, the U.S. is facing not one but two great power competitors and a host of military vulnerabilities, many of which are a direct result of foreign hypersonic capabilities. The instinct held by pro-hypersonic voices to invest in technological solutions to these vulnerabilities is admirable, and perhaps even feasible, but it has been directed at the wrong weapons program. As our BMD capabilities become increasingly vulnerable to foreign hypersonic weapons, the U.S. could begin the development of satellite-based missile defense technology designed to target hypersonic missiles in their early boost phase, the expansion of the quantity of ground-based ICBMs in the U.S. arsenal that can act as “sponges” for missiles in the event of a nuclear first strike, or a number of other technical solutions to the problems posed by hypersonic weapons in the hands of U.S. adversaries. [22; 23] While the potential existence of these solutions is a cause for optimism, they will inevitably be both technically challenging and exceptionally expensive, and U.S. resources are finite. Given that this is the case, the litany of problems attached to an American hypersonic weapons program, ranging from an unjustifiably high price tag to operational obsolescence in nearly all foreseeable future conflicts to potential nuclear escalation due to warhead ambiguity, should be more than enough to dissuade policymakers from investing in further development of hypersonic technology. With challenges of the scale we are facing on the horizon, the U.S. cannot afford to pour billions of dollars into a weapons system that is at best strategically ineffective, and at worst actively destabilizing.

Sources

[1] Woolfe, Amy F. “Conventional Prompt Global Strike and Long Range Ballistic Missiles: Background and Issues.” Congressional Research Service, Updated 2021, R41464.

[2] Erbland, Peter. “Falcon HTV-2.” Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Archived Research. https://www.darpa.mil/program/falcon-htv-2

[3] United States Department of Defense. “DoD Announces Successful Test of Army Advanced Hypersonic Weapon Concept.” United States Army, November 18, 2011. https://www.army.mil/article/69484/dod_announces_successful_test_of_army_advanced_hypersonic_weapon_concept

[4] United States Air Force. “X-51A Waverider.” https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104467/x-51a-waverider/

[5] Sayler, Kelley M. “Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service, Updated February 13, 2023, R45811.

[6.] Bugos, Shannon. “Congress Authorizes Accelerated Hypersonics Plan.” Arms Control Association, January/February 2022. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2022-01/news/congress-authorizes-accelerated-hypersonics-plan-0

[7.] Verschuren, Sanne. “China’s Hypersonic Weapons Tests Don’t Have To Be a Sputnik Moment.” War on the Rocks, October 29, 2021. https://warontherocks.com/2021/10/chinas-hypersonic-missile-tests-dont-have-to-be-a-sputnik-moment/

[8.] Detsch, Jack. “U.S. Missile Defense Is Cruising for a Bruising.” Foreign Policy, July 14, 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/14/u-s-missile-defense-is-cruising-for-a-bruising/

[9] Kerr, Paul K. “2022 Nuclear Posture Review.” Congressional Research Service, December 6, 2022, IF12266.

[10] Kroenig, Matthew. The Logic of American Nuclear Strategy: Why Strategic Superiority Matters. Oxford University Press, February 15, 2018.

[11] Wilkening, Dean. “Hypersonic Weapons and Strategic Stability.” Survival, Vol. 61, Iss. 5, September 17, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1662125

[12] Lee, Carrie A. “Technology Acquisition and Arms Control: Thinking Through the Hypersonic Weapons Debate.” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 4, Iss 5, Fall 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/43939

[13] Cummings, Alan. “Hypersonic Weapons: Tactical Uses and Strategic Goals.” War on the Rocks, November 12, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/hypersonic-weapons-tactical-uses-and-strategic-goals/

[14] Congressional Budget Office. “U.S. Hypersonic Weapons and Alternatives.” January 31, 2023. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58255

[15] Cancian, Mark F. Et al.. “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, January 9, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan

[16] Timbie, James Et al.. “A Large Number of Small Things: A Porcupine Strategy for Taiwan.” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 5, Iss. 1, Winter 2021/2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/21613

[17] Heckmann, Laura. “Report Casts Doubt on Value of Hypersonic Weapons.” National Defense Magazine, January 31, 2023. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2023/1/31/hypersonic-weapons-development-faced-with-technological-challenges-report-finds#:~:text=The%20report%20estimated%20that%20acquiring,billion%20for%20comparable%20hypersonic%20missiles.

[18] Acton, James M. “Prompt Global Strike: American and Foreign Developments.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Testimony before the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, December 8, 2015.

[19] Klare, Micheal T. “An ‘Arms Race in Speed’: Hypersonic Weapons and the Changing Calculus of Battle.” Arms Control Today, Vol. 49, No. 5, June 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26755134

[20] Talmadge, Caitlin. “Would China Go Nuclear? Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States.” International Security, Vol. 41, Iss. 4, Spring 2017. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00274

[21] Acton, James M. “The Arms Race Goes Hypersonic.” Foreign Policy, January 30, 2014. https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/01/30/the-arms-race-goes-hypersonic/

[22] Sugden, Bruce M. “Nuclear Operations and Counter-Homeland Conventional Warfare: Navigating Between Nuclear Restraint and Escalation Risk.” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 4, Iss. 4, Fall 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/17497

[23] Kroenig, Matthew Et al.. “The Downsides of Downsizing: Why the United States Needs Four Hundred ICBMs.” The Atlantic Council, March 29, 20221. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/the-downsides-of-downsizing-why-the-united-states-needs-four-hundred-icbms/