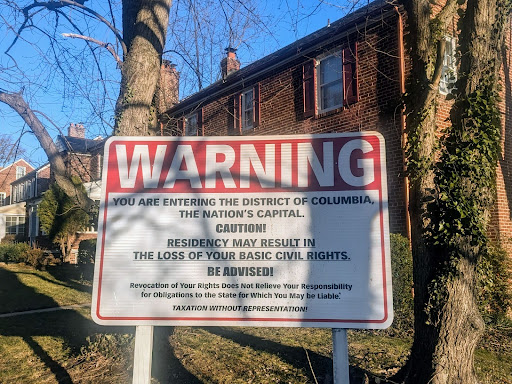

Second-Class Citizenship in the Nation’s Capital: How the D.C. Statehood Movement is Fighting to Bring Democracy Closer to Home

Photographed by: Aimee Friloux

The United States is the only democracy in the world that disenfranchises its citizens on the basis of their residency in its capital city, Washington, D.C. If a Washingtonian were to move to any of the U.S.’ 50 states, they would be afforded the kind of democratic representation they could only dream of having in their home district: 2 senators, 1 representative per every 765,000 people, state and local legislatures and budgets that are not controlled by elected officials who did not earn their vote, and a say in the electoral college proportional to the population of the state in which they live [1]. Though the consequences of D.C.’s lack of statehood are clearly antithetical to the U.S.’ founding principles, its status as a district continues to be justified by the same arguments that motivated the “District Clause” of the Constitution, which forbids statehood for the nation’s capital. In spite of their archaic justifications, it would appear as though opponents of D.C. statehood are invincible because they can employ the most powerful argument of all: D.C. statehood is unconstitutional. But D.C. statehood is not unconstitutional, and the District Clause is nothing more than a convenient cover argument for their partisan interest: to maintain political power, even at the cost of U.S. democratic ideals.

Article I, Section 8, clause 17 of the Constitution, otherwise known as the District Clause, states that a district “not exceeding ten miles square” shall “become the seat of government of the United States,” with Congress “[exercising] exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such district,” therefore barring the nation’s capital from all privileges afforded to states by the Constitution [2]. James Madison justifies the clause in Federalist 43 by arguing that it is “an indispensable necessity of complete authority at the seat of government…without it…the public authority might be insulted and its proceedings interrupted with impunity…equally dishonorable to the government and dissatisfactory to the other members of the Confederacy” [3]. In other words, if D.C. were a state, its residents would be too close to the federal government not to have undue influence on it—even though some residents of Maryland and Virginia are closer to downtown D.C., where government buildings are housed, than residents in the southeastern quadrant of the city. The most logical approach to attacking Madison’s argument is to beg the question: what is the modern-day equivalent of proximity? According to OpenSecrets, a nonprofit organization that publishes frequent reports on campaign finance and lobbying, federal lobbying expenditure reached a record-high 4.2 billion dollars in 2023, a number that has been growing consistently since 2015. Pharmaceuticals, electronics manufacturing, and insurance outspent all other industries in that same year [4]. This outside influence on the legislative process is not what Madison wanted, and it is also not what Madison predicted: special interest groups, not individual citizens who are most proximal to the seat of the federal government, are afforded special privileges over “other members of the Confederacy.”

As archaic as equating physical proximity to power may seem today, when communication is not restricted by geographical location, the argument has become the backbone of the conservative movement against D.C. statehood. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, strongly opposes D.C. statehood on the basis that the founders “understood that the seat of our federal government should be a place where all Americans can conduct our nation’s business free from the influence of any particular state” [5]. Ironically, the conservative argument perfectly encapsulates why mandating D.C. be a district is not an appropriate solution to Madison’s concerns: the seat of the federal government is not a place where all Americans can conduct our nation’s business. That right was made exclusive to residents of states.

The full enfranchisement of Washingtonians is substituted for their ability to elect one delegate—not representative—to the House, as well as members of the Council of the District of Columbia, which is responsible for the drafting of local legislation—but not its approval. The delegate can draft legislation and debate on the House floor but is not allowed to vote as mandated by the Constitution, making them essentially powerless. D.C.’s delegate is currently Eleanor Holmes Norton, who has been in office since 1991. An unshakable proponent of D.C. statehood, Norton makes the same statement to Congress every year as the tax filing deadline approaches: D.C.“pays more federal taxes per capita than any state and more federal taxes overall than 19 states” [6]. Even so, Washingtonians have no say in “federally appointed positions, such as the president’s cabinet or those serving as U.S. ambassadors to foreign countries,” or federal or Supreme Court judges due to their lack of representation in the Senate [7].

While D.C.’s right to elect one delegate to the House is enshrined in the Constitution, its local government was not established until 1973 with the passage of The District of Columbia Home Rule Act [8]. While the act allows residents to elect a mayor and a 12-member legislature, the Council of the District of Columbia, D.C.’s local government remains “subject to the whims of the federal government where Congress interferes with…local laws, local funding, and operations” [9]. Unlike states, which are able to pass legislation without congressional interference, “unique to the District of Columbia, an approved Act of the Council must be sent to the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate for a period of 30 days before becoming effective as law...During this period of congressional review, Congress may enact into law a joint resolution disapproving the Council’s Act, with the President having the final say in whether the Council’s bill will be blocked by Congress” [10]. In sum, the fate of local laws that impact D.C. residents’ lives are in the hands of representatives they never elected; even D.C.'s local budget is subject to the congressional appropriations process. In a congressional hearing on D.C. statehood in 2023, Mayor Muriel Bowser reminded Congress of the absurdity of congressional interference with D.C.’s local affairs: “I don’t have to come here, to talk to you, to talk to the residents of D.C. I talk to them daily” [11]. Beyond the issues of taxation, representation, and legislation, D.C. has sent over 200,000 men and women to fight for the U.S. abroad since World War I, and the state-by-state death toll in Vietnam places D.C. above 10 states [12, 13]. For centuries, D.C. residents have been willing to fight for their country more than their country has been willing to fight for them.

Not until 1961, with the ratification of the 23rd Amendment, was D.C. afforded three electoral votes. The number will not grow with D.C.’s population, however, since the amendment mandates that D.C.’s electoral vote count match that of the least populous state in the country [14]. The 23rd Amendment also fails to address the case of an electoral college tie; it remains that each state has one tie-breaking vote, except for D.C. [15]. Blindspots such as these highlight why D.C. must be granted statehood outright, rather than being drip-fed democracy.

Regardless, the hill that lawmakers must climb to grant D.C. statehood is a steep one, both politically and constitutionally—although the former is the real barrier. June 2020 marked the first time in history that real legislative progress was made toward D.C. statehood, with the passage of H.R. 51 in the House. Also known as the Washington, D.C. Admission Act, the bill was initially introduced by delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton. Remaining true to the Consitution’s District Clause, H.R. 51 advocates for most of the current District of Columbia to become a state, to be known as the Douglass Commonwealth, while the rest remains a district [16]. Many legal scholars and advocates of the bill alike argue that shrinking the district is constitutional since no minimum size is explicitly specified in the District Clause; the district must only satisfy the requirement of “not exceeding a ten miles square” [17]. The main constitutional challengers to H.R. 51 seem to concede this point in choosing to argue that the District Clause limits “Congress’ power to change the seat of government once it is established,” instead of directly attacking the new district’s size [18]. However, nothing related to size changes is explicitly stated in the clause. In fact, history has proven that modifications to the district are possible: “Congress…reduced the size (and changed the shape) of the Federal District” in 1846, when a portion of D.C. was retroceded to Virginia [19]. The new district that H.R. 51 calls for would consist of “the White House, the Capitol Building, the U.S. Supreme Court Building, principal federal monuments, and the federal, executive, legislative and judicial office buildings located adjacent to the National Mall and the Capitol Building,” or all non-residential areas [20]. By not converting the entirety of D.C. into a state, advocates argue that H.R. 51 further satisfies the portion of the District Clause that assigns Congress exclusive legislative authority over the seat of the federal government. In line with the privileges afforded to states by the Constitution, H.R. 51’s success would allow for the first-time election of “two Senators and one Representative for [the] Douglass Commonwealth,” while compromising with the federal government in other necessary areas, such as maintaining “federal authority over military lands and certain other property within Douglass Commonwealth,” and “[prohibiting the] Douglass Commonwealth from imposing taxes on federal property except as Congress permits” [21].

Working around the District Clause is uncharted legal territory, but H.R. 51 stands on solid constitutional ground nonetheless. The “Admissions Clause (also known as the New States Clause) in Article IV, Section 3, clause 1” gives Congress the power to admit new states to the Union, which has been done a remarkable 37 times in U.S. history [22]. As a result, the “Douglass Commonwealth” would be admitted via the same process that those 37 states underwent; D.C. statehood is not the impossibility opponents attempt to characterize it as. With the Admissions Clause comes the promising possibility that constitutional challenges to H.R. 51 would be dismissed by courts outright on the basis that “the District’s political status is a ‘political question’ unsuited for resolution by the judicial branch” [23]; Article III, Section 2, Clause 1 of the Constitution, otherwise known as the Political Question Doctrine, “limits the ability of the federal courts to hear constitutional questions,” when the power to resolve the issue at hand is explicitly granted to the Executive or Legislative branches by the Constitution [24]. Armed with the combination of the District Clause, which fails to specify a minimum size requirement, and the Admission Clause, which allows Congress to admit new states, proponents of D.C. statehood are in a strong position to fight back claims that H.R. 51 is unconstitutional.

Ironically, the first win for the D.C. Statehood movement is also what poses the biggest challenge to H.R. 51: the 23rd Amendment. Even if H.R. 51 were to pass the Senate, which it has yet to achieve, and fend off constitutional challenges, which it has yet to face, Congress would need to repeal the 23rd Amendment. Otherwise, the “Twenty-Third Amendment would continue to operate as written, potentially giving state-like electoral power to the greatly limited population of the reduced Federal District, should there be any such population” present [25]. This is why H.R. 51 includes in its provisions “expedited consideration in both the House and Senate of a joint resolution proposing repeal”; however, this “does not guarantee that both houses would ultimately vote in favor…or that three-fourths of states would promptly ratify the repeal” [26]. H.R. 51’s reliance on the repeal of the 23rd Amendment gives opponents of D.C. Statehood an easy way to kill the bill. While passage of H.R. 51 in the House and Senate only requires a simple majority, repeal of a constitutional amendment requires two-thirds support in both the Senate and the House. Assuming a slim majority is assembled in both chambers to pass H.R. 51, opponents could quickly erode any support gathered for the bill by leveraging their refusal to repeal the 23rd Amendment. After all, granting 3 electoral votes to a newly shrunken district is akin to granting whichever political party holds the White House in a given presidential election 3 electoral votes toward their own re-election—which neither party would approve of.

Ratification of the repeal by three-fourths of states is an even steeper climb. It is a well-known fact that majority-Republican states enjoy electoral college power disproportionate to their population size, and admitting the “Douglass Commonwealth” as a state has prompted political outrage from Republican state officials [27]. Following the passage of H.R. 51 in the House for the second time in the bill’s history in 2021, a total of 22 state attorneys general signed a letter sent directly to President Biden and written by the Attorney General of South Carolina, Alan Wilson, who expresses vehement opposition to the bill in his writing. All twenty-two attorneys general are from states that are either Republican strongholds, such as Mississippi, Alabama, and Kentucky, or states with slimmer but still clear Republican majorities, such as Ohio and Georgia. The letter wastes no time in declaring H.R. 51 unconstitutional, using the same argument that has already been disproven by legal scholars: the district is not allowed to change shape. This weak constitutional argument at the beginning of the letter is merely an attempt to soften the harshness of what is written towards the end. As Alan Wilson puts it, “[H.R. 51] is bad policy. Its enactment would be antithetical to our democratic representative republic, and it would constitute an unprecedented aggrandizement of an elite ruling class with unparalleled power and federal access” [28]. The “elite ruling class” that Wilson is referring to is no secret: Democrats account for nearly 78 percent of registered voters in D.C. in 2024, and the district consistently votes blue in presidential elections [29]. The letter reveals what opponents of D.C. statehood—Republicans—are truly fighting against: a loss of their own political power. And they are more than willing to improperly use the Constitution to ward off that criticism. Republicans even attempt to claim that admittance of the “Douglass Commonwealth” as a state is antithetical to representative democracy when their own agenda is the true antithesis. In Congress, Republicans have devolved away from the constitutional argument and toward making almost no effort to hide that their reasons for rejecting H.R. 51 are political. Upon passage of H.R. 51 in the House in 2021, Republican Representative James Comer of Kentucky declared that “‘America’s federal government should be ‘of the people, by the people, for the people,’ but with H.R. 51 America’s government will become ‘of the Democrats, by the Democrats, for the Democrats.’ This bill is not about voting representation—it is about consolidating liberal power” [30]. H.R. 51 was subsequently killed in the Senate along party lines.

The Republican playbook on D.C. statehood is not well-written: make a weak constitutional argument, then sound the alarm on the impending Democratic takeover. But it does not have to be when the votes are not there to push H.R. 51 to the finish line. As a result, D.C. has been inching towards enfranchisement for decades; an unavoidable slow-crawl, since any proposal presented needed to be made digestible for Republicans. First, the 23rd Amendment in 1961, which does not allow D.C.’s electoral vote count to grow with its population. Then the Home Rule Act of 1973, which keeps the Council of the District of Columbia on a tight congressional leash. However, since Delegate Norton’s first introduction of H.R. 51 in 2020, the movement for D.C. Statehood has gained momentum, and Republicans are scrambling to maintain a justification for their decision to perpetuate the disenfranchisement of over 700,000 U.S. citizens on the basis of their likelihood to vote for an opposing political party. Norton reintroduced H.R. 51 to the House in 2023. Even if it passes in the House for the third time, it will not pass in the Senate. And with incoming Republican majorities in both the House and Senate, H.R. 51 is unlikely to see passage for at least the next two years. D.C. houses the nation’s democratic institutions. But for its residents, democracy could not be further from home.

Sources

[1] Chinni, Dante. “The Country’s Population is Growing- but Congress is Standing Still.” NBC News. September 3rd, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/data-download/nations-population-growing-congress-standing-still-rcna103142

[2] “The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription.” The National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

[3] “The Federalist Papers: No. 43.” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed43.asp

[4] Massoglia, Anna. “State and federal lobbying spending tops $46 billion after federal lobbying spending broke records in 2023.” Open Secrets. January 26th, 2024. https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2024/01/state-and-federal-lobbying-spending-tops-46-billion-after-federal-lobbying-spending-broke-records-in-2023/

[5] Smith, Zack. “No to D.C. Statehood.” The Heritage Foundation. September 11th, 2023. https://www.heritage.org/the-constitution/commentary/no-dc-statehood

[6] “Norton Says Federal Tax Filing Deadline is Reminder that D.C. Residents Remain Under Taxation Without Representation.” Norton.house.gov. April 15th, 2024. https://norton.house.gov/media/press-releases/norton-says-federal-tax-filing-deadline-reminder-dc-residents-remain-under

[7] Government of the District of Columbia. “Frequently Asked Questions about Statehood for the People of DC.” https://statehood.dc.gov/page/faq

[8] “D.C. Home Rule.” Council of the District of Columbia. https://dccouncil.gov/dc-home-rule/

[9] Government of the District of Columbia. “Why Statehood for D.C.” Statehood.DC.gov. https://statehood.dc.gov/page/why-statehood-dc

[10] “How a Bill Becomes a Law.” Council of the District of Columbia. https://dccouncil.gov/how-a-bill-becomes-a-law/

[11] “Committee Democrats Demand Statehood for D.C., Defend District’s Right to Home Rule.” Committee on Oversight and Accountability Democrats. May 17th, 2023. https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/news/press-releases/committee-democrats-demand-statehood-for-dc-defend-district-s-right-to-home-rule

[12] Government of the District of Columbia. “Why Statehood for D.C.”

[13] “Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics.” The National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics

[14] “23rd Amendment: Presidential Vote for D.C.” National Constitution Center. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/amendments/amendment-xxiii

[15] “The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription.” The National Archives.

[16] “H.R.51 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Washington, D.C. Admission Act.” Congress.gov, Library of Congress. September 8th, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/51

[17] “The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription.” The National Archives.

[18] Schwartz, Mainon. “D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations for Proposed Legislation.” Congressional Research Service. May 12th, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47101

[19] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[20] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[21] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[22] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[23] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[24] “Overview of Political Question Doctrine.” The Constitution Annotated, Congress.gov, Library of Congress. https://constitution.congress.gov/about/constitution-annotated/

[25] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[26] Mainon,“D.C. Statehood: Constitutional Considerations.”

[27] “Representation in the Electoral College: How Do States Compare?” USA Facts. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/electoral-college-states-representation/

[28] “DC Statehood Letter as Sent.” Texas Office of the Attorney General. https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/sites/default/files/images/admin/2021/Press/DC%20Statehood%20letter%20as%20sent%20(02539672xD2C78)%20(002).pdf

[29] “Monthly Report of Voter Registration Statistics: Citywide Registration Summary as of February 29, 2024.” D.C. Board of Elections. February 29th, 2024. https://dcboe.org/getmedia/2a5e33e8-90ef-430f-b91f-64372b4eb29d/Data-Statistics-Report-02_2024.pdf

[30] “Comer: Democrats’ Arguments for H.R. 51 Don’t Hold Any Water.” Committee on Oversight and Accountability. April 14th, 2021. https://oversight.house.gov/release/comer-democrats-arguments-for-h-r-51-dont-hold-any-water/