Reassessing the North Korean Nuclear Threat

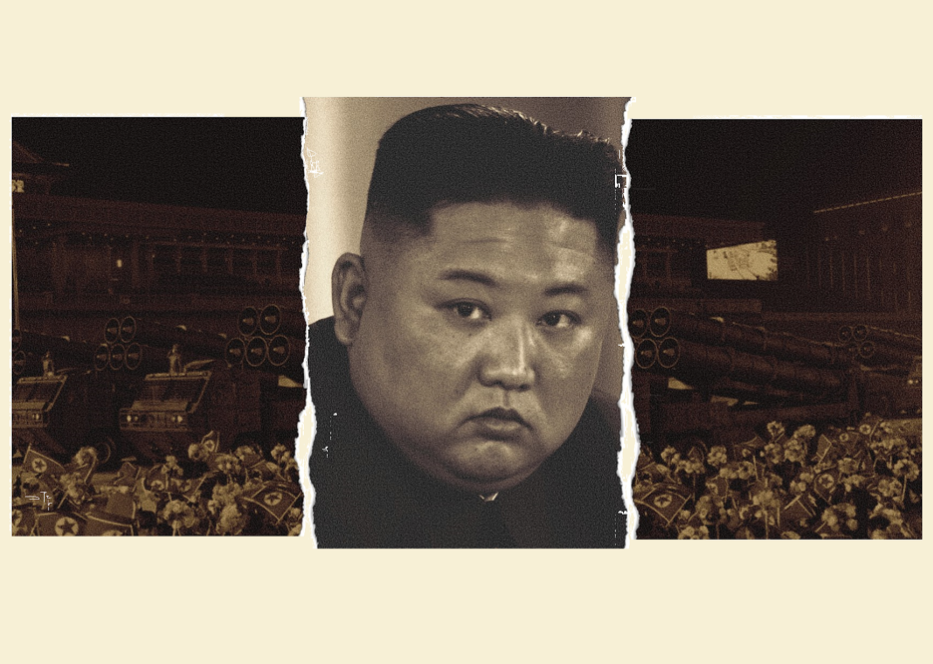

Foreign policy pundits have paid acute attention to Chinese and Russian nuclear enhancements over the past decade as geopolitical concerns and technological capacities have increased. Just as considerable is the North Korean nuclear threat. Despite the DPRK’s nuclear program creating vast implications for international security and foreign policy, the country has received little sustained attention. Yet, viewing Kim Jong-un’s North Korea as a limited nuclear power instead of a formidable nuclear force could not be more dangerous.

On Thursday, the DPRK displayed new submarine-launched ballistic missiles in a parade, projecting Kim Jong-un’s ambitions to begin testing nuclear weapons once again. Any time a state overtly augments their arsenal, officials need to secure an explanation as to why an already nuclear-powered country is seeking to expand, the risks involved, and the larger threats to the global nuclear order.

Numerous opinions exist as to why North Korea is motivated to nurture their nuclear arsenal. Of considerable importance is the feeling of vulnerability. Combined with nationalism, nuclear weapons in North Korea served as a bargaining chip toward normalization with the United States and its NATO allies, on top of ceasing its dependence on China. Pyongyang’s careless nuclear ambitions, however, have tainted attempts at normal relations with the West, resulting in a pivot towards deterrence and increased isolation.[1]

This came to a head in September of 2016 when the North conducted a series of long-range and intermediate-range missile tests, which affirmed Washington officials’ fears that the North’s ultimate goal is to reliably target the United States with nuclear weapons. The DPRK’s attempts to conduct itself as a responsible nuclear weapons state failed, and produced increased vulnerability and a heightened reliance on nuclear weapons.

The question becomes when, how, and why would North Korea detonate the bomb. Nuclear scholar Michael D. Cohen suggests that Kim Jong-un is expected to use nuclear force if placed in a situation in which he feels he has no control over nuclear war or regime change from ensuing.

Compellence vs Deterrence

An important aspect of this theory rests on Thomas Schelling’s concept of deterrence versus compellence. While compellence seeks to alter the status quo, deterrence seeks to maintain it.[2]

In the case of nuclear-armed states, compellence rarely works. Mao Zedong acquiring nuclear weapons did not settle boundaries over the Ussuri River with the Soviet Union. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal did nothing to change the disputes occurring in Kashmir. And India’s nuclear arsenal has proved weak in stopping terrorists in Pakistan from attacking India. Yet, compellence is part of King Jong-un’s ambitions. Pyongyang has lived with the status quo since the end of the Cold War, which means the country has battled to retain credibility against American and NATO superiority.

Why would North Korea embark on an extraordinarily complex mission to alter the status quo? The simple answer is that it has worked in limited fashion.

Kim is genuinely paranoid about regime collapse, which makes his nuclear arsenal a crucial tool for preservation. Similar to the tactics of Nikita Khruschev, Kim Jong-un has used calculated brinksmanship to seek negotiated resolutions that, little by little, have been on North Korea’s terms.[3] The North’s nuclear provocations have been routinely followed by about a six month period of dialogue in which the North has gained some sort of concession.[4] It is likely that Kim will continue to use this form of brinksmanship to realize alterations to the status quo until he experiences imminent nuclear war.

Nuclear War

It is commonly said that fear is central to international politics.[5] In the nuclear world, that is highly entertained. The influence of fear on nuclear policy is conditional on beliefs of control: if the perception that control is above zero, which demarcates no control, risk tends to be avoided (though, that decreases the closer to zero one approaches). That means, if Kim Jong-un felt that he had genuine control over nuclear war from ensuing, he would likely show restraint from using nuclear force. On the contrary, if that perception is zero, nuclear weapons would become the last resort to protect the Kim regime, making their use exceptionally likely.[6]

The 2018 false missile alert in Hawaii is an exemplar. First, Washington officials knew that there wasn’t a real attack occurring because America’s highly-advanced sensors would have detected it. Second, officials admitted they had made a mistake when they claimed that North Korean missiles were en route. Lastly, Americans believed that there was no reason why Kim would issue a nuclear war at the time.

If the roles were reversed, however, and Kim Jong-un believed that American missiles were headed towards their country, the outcome would have been devastatingly different. That is because those three steps do not exist in North Korea.

For one, their nuclear sensors are highly-outdated, meaning there is always a level of ambiguity when assessing possible threats. Next, we are dealing with a man who had murdered his half-brother and regularly executes his officials. It would take an incredibly brave officer to admit that he had miscalculated the threat. Finally, to America’s fault, Kim would not have known whether or not Washington was planning to attack because our posture signaled that we would. Trump making an overt threat towards Kim Jong-un by referring to a denuclearization plan as the “Gaddafi model” is a case in point.

How does the North’s display of new weapons fit into this? The parade featured a debut of new weapons systems, of considerable importance are the submarine-launched ballistic missiles and the purported intention to deploy hypersonic missiles.

All of this is likely to signal North Korea as a formidable nuclear power. It is a message to President Joe Biden, who is expected to reaffirm North Korea as a threat, that the North will not tolerate being at the behest of an American-led nuclear order.[7] Indeed, addressing a nuclear North Korea is a strenuous game of chance where each move is rarely absent of consequences. Kim knows this, and appears to be using it to his advantage.

As the North continues enhancing its arsenal with the intent to reach American shores─a scenario that is not an “if” but a “when”─America needs to consider ways to ensure a paranoid Kim retains a sense of psychological security. This would mean coping with a nuclear-armed North Korea. The plan should not be to destroy Kim’s arsenal, as there is no guarantee that every nuclear weapon would be destroyed, especially in a location that outsiders know little about. A preventive strike, moreover, risks Kim believing that the US and their South Korean, Japanese, and NATO allies have unlimited ambitions to see the end of the Kim regime. His options would be limited. The feeling of paranoia would heighten. And it would likely mean that Kim Jong-un would retaliate in some capacity using his nuclear weapons.

All of this is coming to a head at a critical moment for nuclear arms control: Russia declared on Friday that it will remove itself from the Open Skies Treaty, a legacy of the Cold War that fostered important transparency by allowing countries to fly over adversarial territoires to keep track of militaristic movements.[8] It marks yet another US-Russian-led treaty seeing its end. Joe Biden is entering a global nuclear landscape that is looking increasingly grim, which means he has to contemplate which areas he needs to hard-press the DPRK on, and which areas he needs to show diplomacy.

Policy Challenges

America is dealing with an actor who will not willingly give up its nuclear arsenals, nor can any state force them to do so without risking nuclear war. Thus the question becomes how to best work with a nuclear North Korea. We do so by preserving a level of vulnerability while at the same time, allowing Kim to feel as though he has options. While the two seem antithetical, the combination has proved effective in deterring escalations by making states reluctant to use nuclear force.

Communication is key: America needs to disown its ambiguous nuclear doctrine that leaves considerable room for misinterpretation by the North. For example, if the United States declared that any nuclear missiles that approach South Korea or Japan would be destroyed, it would likely deter Kim from using these flight paths.[9] This could help to ensure that Kim retains the belief that he has some control over nuclear escalation if he can better assess America’s nuclear doctrine.

At the same time, Kim needs to know that testing America’s patience is dangerous; he needs to experience fear of imminent nuclear war to prevent him from continuing nuclear provocations, such as careless testing of weapons.

Kim Dong-yub, an analyst at Seoul’s Institute for Far Eastern Studies and a former military official who participated in inter-Korean military talks, said it would take “considerable time” for North Korea to overcome financial difficulties to produce such systems.[10] Washington needs to use that time wisely.

America and its allies need to foster considerable dialogue with the North and conjure policy outlines that would address what is a growing threat of nuclear war issued by North Korea. Policy makers should approach the North not as a rising power, but one that has already reached nuclear formidability. There is a window of opportunity for the United States to foster bilateral and multilateral negotiations exchanging the dismantlement of some nuclear abilities for sanctions relief. While this would be imperfect, as in any game that balances chance with tactic, it is how one recognizes those apertures and works around them.

“They have seen Libya, they have seen Afghanistan, they have seen Iraq, they have seen Ukraine, Crimea. North Korean leaders have always believed nuclear arms are the only guarantee of their political and perhaps physical survival,” said Andrei Lankov, a professor at Kookin University in Seoul.[11] President Biden needs to hard press his officials to increase strategic dialogue with the North and start commencing confidence building measures.

The North’s military parade on Thursday was more than a signal of great power. While perceptions of the threat of North Korea have been overshadowed by those of Russia and China, America needs to reassess the North Korean nuclear threat and engage quickly on policy procedure to handle what is becoming an increasingly complex entanglement with one of the most secretive countries in the world.

Sources

[1] Daniel Wertz, “The US, North Korea, and Nuclear Diplomacy,” The National Committee on North Korea, October 2018

[2] Michael D. Cohen, “North Korea and Nuclear Weapons.” Georgetown University Press. p. 57

[3] Ibid, p. 59

[4] Victor Cha, “The impossible state: North Korea, Past, Present, and Future.” p. 23

[5] Shiping Tang, “Fear in International Politics: Two Positions.” International Studies Review, 452

[6] Cohen, p. 63

[7] Mike Yeo and Kim Tong-Hyung. “See the Weapons at North Korea’s Latest Military Parade.” DefenceNews. 15 January 2021. https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2021/01/15/see-the-weapons-at-north-koreas-latest-military-parade/?utm_source=clavis

[8] Anton Troianovski and David E. Sanger, “Russia to Exit Open Skies Treaty, Escalating Military Rivalry With U.S.” The New York Times, 15 January 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/15/world/europe/russia-open-skies-treaty-biden.html

[9] Cohen, p. 67

[10] Yeo and Tong-Hyung

[11] Simon Denyer and Simon Denyer, “North Korea’s Kim Could Be Planning Missile Launch To Welcome Biden Administration.” The Washington Post. 18 January 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/north-korea-biden-missile-test/2021/01/18/25268116-594f-11eb-a849-6f9423a75ffd_story.html