Politics On Hiatus: Is Neoliberal Hyper-Individualism Antithetical to Collective Action?

Introduction

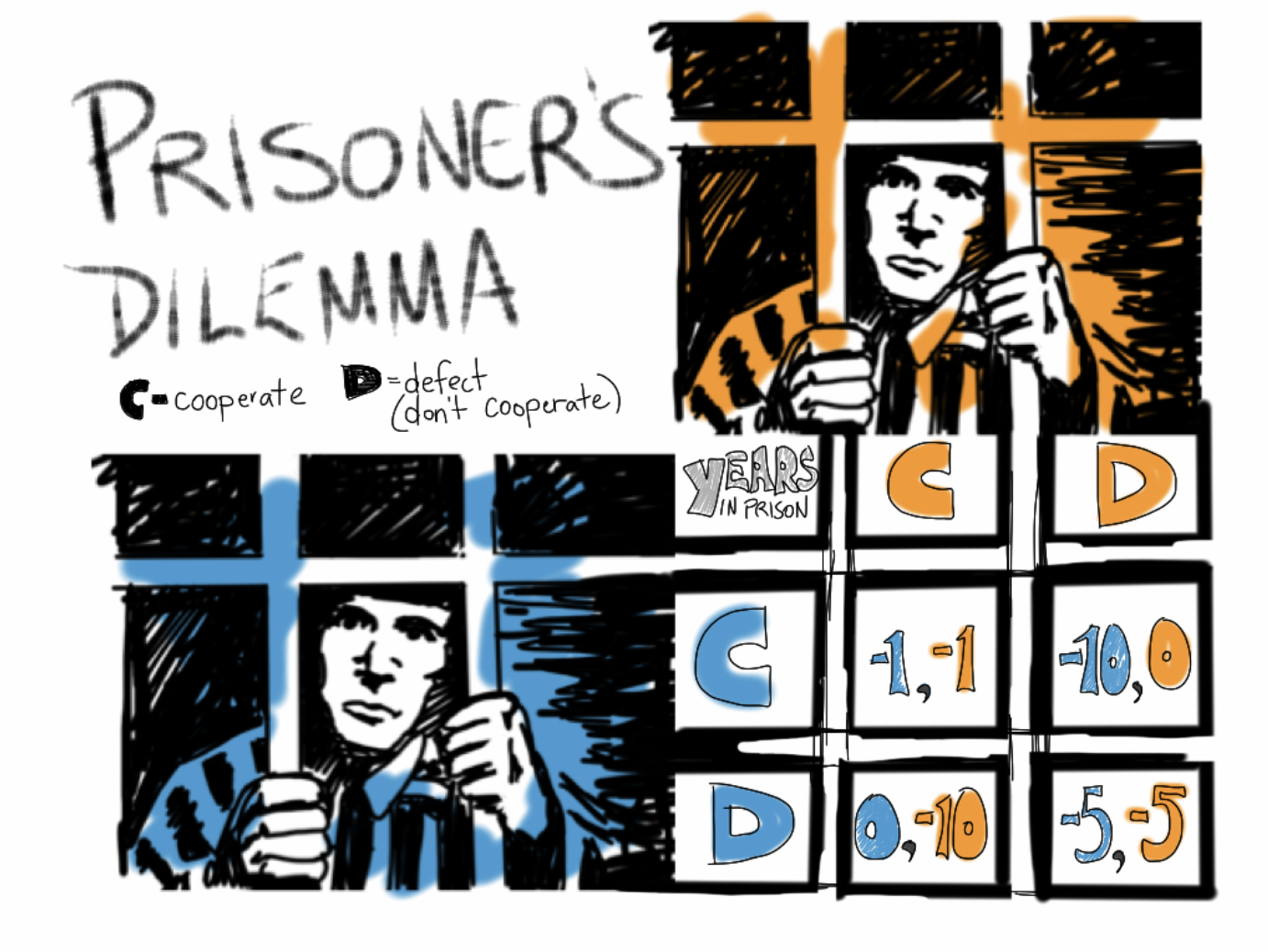

In many introductory political science classes, students are taught the concept of the prisoner’s dilemma. Two prisoners are interrogated separately, with the option either to accuse the other or stay silent. If both remain silent, they both receive a short sentence. If both talk, they both receive a medium sentence. Yet if only one talks, they go free, while the accused prisoner receives a long sentence. The lesson students are intended to draw from this is that, while deciding in isolation, you’re better off betraying the other prisoner: the best overall outcome can only occur with coordination. From this, professors explain why we have politics in the first place: to achieve the greatest collective benefit by putting some of our own interests aside for the betterment of the group.

Unfortunately, coordination cannot always occur on a society-wide basis because many questions do not have an answer that is objectively best for everyone. For example, putting aside ethical implications, decisions such as whether to cut drug prices, dismantle apartheid policies, or phase out fossil fuels benefit one stratum of society at the expense of another. To coordinate the actions of these strata such that legislators and armies could represent them, political parties constructed ideology: a word initially defined as “an interplay of ideas, belief systems and opinions between the dominant class in the society and those that seek to displace them [1].” Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, ideology served as the backbone of political movements and provided citizens with reason to concede some of their individual desires for the pursuit of common goals.

However, with the global expansion of neoliberalism at the end of the Cold War, ideological competition has ceased to drive both domestic and international affairs. As Western powers leveraged control over foreign loans to require the implementation of austerity measures, national economic policymaking in the global periphery was supplanted by the impositions of IMF economists [2]. Governance became less driven by ideological reasoning than raw economic remunerability, derived from the ability to integrate within the only remaining world system. Introspectively, the neoliberal consensus prioritizes individual isolation and achievement to a point where philosopher Byung Chul-Han believes that “no political we is even possible that could rise up and undertake collective action” [3]. In recent decades, when we have American aerospace engineering students joking about “selling their soul” to a cause impersonal to them, a line in the Chinese Communist Party centered vaguely on “doing what works,”—and the imam of the Masjid Al-Haram instructing citizens to leave the fitna of world affairs to their rulers—much political communication has been stripped of its theoretical undertones [4,5]. There comes a point where we must ask ourselves, what collective action can emerge in a world of ideological homogenization and uncontested hyper-individualism?

Implications In Practice

In the past decade, there has certainly been ample energy, especially among Generation Z, to achieve political change. Inspired by conditions of economic hardship, corruption, and state repression, protest movements around the world had more than doubled from the 2000s to the 2010s [6]. While many demonstrations in developed countries—such as those concerning climate and Palestinians—have yielded minimal concessions, popular movements in the rest of the world successfully toppled regimes from Kyrgyzstan to Nepal to Sudan. Qualitatively, however, there is something different about political movements in the modern world: decentralization and reliance on social media [7]. While popular support and digital engagement are essential for any successful movement, the absence of a professional, ideologically driven organizational apparatus has limited Gen-Z’s ability to reform societies after the removal of a regime.

Most recently, unrest in Madagascar over immense inequality and corruption led to the resignation and exile of former President Andry Rajoelina. Madagascar Tribune reported thirteen days before protests began that the country possessed “a fragmented structure where the Francophone elite remains connected to Paris and multinational corporations, while the majority lives on the margins of the state and its norms” [8]. On September 25, 2025, protests over electricity and water shortages erupted in the capital. By October 11, branches of the military had joined the protests, causing Rajoelina to resign and flee to France. Soon after his departure, the action died down, and the military restored order without addressing the aforementioned root problems. Without clear leaders, the protestors were reported by the country’s leading newspaper as “making repeated appeals to political parties, unions, and civil servants for support, without real success,” raising questions about this generation’s “ability to transform its anger into a structured political demand ” [9].

In 2023, a mass movement in Bangladesh overthrew the government of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina. Bengali scholar Muhammad Rashiduzzaman observed that Hasina’s supposed “secular liberalism” was merely “a cover for authoritarian and dynastic rule backed by India” [10]. Similar to Madagascar, the protest movement that deposed Hasina lacked a unifying doctrine beyond opposition to discrimination and encompassed a mass of both moderate and radical citizens. Once Hasina was removed from power, the student leaders of the protests stated they had “no other enemies” beyond Hasina’s Awami League, which deprived the movement of its initial points of unity [11]. Instead, the Jamaat-e-Islami party—noted by Rashiduzzaman for its “cadre and Islamic creed”—filled the “void caused by the rising distrust and unpopularity of liberal and secular parties” [12]. Jamaat’s success in consolidating power underscores the importance of maintaining a firm organizational schema and a clear ideological line—both absent among other factions of the original protests—to achieve tangible change.

While U.S. elections are not always representative of global political trends, recently elected New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani illustrates the effects of individualism on electoral politics quite well. When his rival Andrew Cuomo confronted him in the debate about previous vocal support for Palestine, Mamdani downplayed the role of ideology in day-to-day governance, stating that “the questions we’ll be asking the sanitation commissioner will be about garbage” [13]. Though some pragmatism and adaptability are necessary in any successful political movement, their use to deflect or distract from questions of principle reflects the contemporary avoidance of ideologically driven messaging. The New York Times, after conversing with several youth volunteers and supporters deemed critical for his victory, concludes that “spiritually unmoored and socially stunted by the pandemic, young New Yorkers needed a reason to get out of the house [14].” As the mayor-elect distanced himself from earlier ideological positionings, he wasn’t primed to lose the effort and support of the many voters and volunteers who would retain the friends and fulfillment they found in his campaign. Mamdani’s ideological elasticity is not merely a reflection of him, but of a broader political environment focused more on individual fulfillment than the realization of collective, ideological goals.

Theoretics

During the twentieth century, the ideologies of liberalism, communism, and fascism—each represented by a bloc of states—struggled to be the dominant ideology in the world. Ideology provided states with both a justification for their actions and a means to mobilize their populations, taking command of various spheres of society from science to culture. Oppenheimer, for one, believed the greatest contribution of his atomic bomb was “new arguments for arrangements, for hopes, that existed before this development took place” [15]. Conversely, Nazi ideology stifled technological progress in various non-military sectors of production with the goal of preventing these new arrangements from coming about. A 1934 Economist report directly from Berlin states that “party ideology rejects machinery; and government prohibitions against its use increase” [16]. Concurrently, there were already concerns about the deprioritization of ideology across the world. In his famous 1961 farewell address, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in some ways predicting the concept of “selling one’s soul to Lockheed Martin,” remarked that the unchecked power of the military-industrial complex would endanger the liberal values of government policy [17]. In the communist camp, Stalin noticed an emergence of representatives and bureaucrats who “did not want to be bothered with ideology, education, and political mass campaigns” [18]. While the respective ideologies of these states varied drastically, they shared the same goal of keeping politics in command of national affairs.

With the post-Cold War transition to a unipolar liberal world, politics has fallen out of command across the world. As left-wing organizations fizzled out from Mozambique to South Yemen to Nicaragua, dissatisfaction with the status quo grew disorganized and spontaneous. Without nationwide exposure through organized partisan action, Lenin observed that even in contexts of mass discontent, populations did not develop a comprehensive political consciousness until it was first propagated by an active party [19]. Indeed, this lack of a unified political consciousness has proved detrimental to the efforts of the aforementioned Gen Z protests in enacting structural reforms. Conversely, the establishment has reflected a comparable absence of ideological adherence. Dissent Magazine noted in 2021 that modern liberals “don’t embrace social and economic rights with the same zeal as their predecessors” [20]. Without significant competition on the world stage, liberalism appears to transform from a distinct ideology into mere reality.

Additionally, the ruling neoliberal doctrine has been noted for propagating a consciousness of isolated individuals entirely responsible for their own outcomes [21]. Individualism at the personal level has indeed risen in every corner of the globe over the past four decades, per a 2017 study in Psychology Today [22]. The study associates much of the variation in the expansion of individualism with socio-economic development and highlights that growth often preceded a rise in individualist practices and values. Yet considering that this trend skyrocketed in the economically stagnant countries of Eastern Europe, and fell in then-rapidly developing China, economic growth is far from the only causal factor. As former diplomat-turned-analyst Joseph Nye asserted, the intentional projection of the United States’ soft power through economic and cultural exports reshaped conceptions of individual and collective identity around the world [23]. Regarding civic matters, neoliberalism has reframed politics around the world not as a struggle between groups and their representative ideologies, but as an intercourse between individual interests and viewpoints.

The effects of this new, individualist outlook on politics were brilliantly displayed in the former Soviet Union. Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich described how old visions of a communist society had transformed into “new dreams of building a house, buying a decent car, and planting gooseberries” [24]. Russian political strategist Evgeny Suchkov asserts that the country’s ruling United Russia party is fundamentally non-ideological, designed to unite members under support for leaders and policies rather than ideas [25]. In synthesizing the seemingly contradictory trends of social conservatism, foreign expansionism, and economic liberalism, the party disregards the past necessity of a theoretical unifying foundation in rallying support.

Undoubtedly, socio-economic development to the level where people have the ability to make their own life choices—where women can have careers and children think for themselves—is objectively beneficial. To some degree, individualist tendencies are necessary for achieving a healthy society. However, a sum of individuals working only towards their concurrent yet uncoordinated dreams of ‘gooseberries and cars’ is—as popular movements in Madagascar and Bangladesh have shown—less inclined to achieve systemic change.

The End Of History?

It is an incorrect assumption that the temporary sidelining of partisan politics signals that we have reached what some deem the “end of history.” In his respectively named book, Francis Fukuyama stated that liberalism would immortalize itself by resolving societal “contradictions” that led to its unraveling in the past [26]. As we have seen with the motivating factors of Gen Z protests, these contradictions have only sharpened in a multitude of nations. Ideology, as it is, simply exists to transform this unrest into organized action capable of systemic restructuring. While Fukuyama asserted that the role previously filled by ideology would fall to “economic calculation [and] the endless solving of technical problems,” new political questions, such as that of artificial intelligence’s role in society, have emerged with no “best for everyone” answers [27]. The question of the present is whether individual discontent with the status quo will be directed into collective action or dissipate amidst disunity. It will be answered by both the organizational tactics of political movements and a broader conception of politics at large as a collective rather than individual struggle. Indeed, changes in the world economy, class relations, and digital connectedness would give rise to different forms of organization than were observed in the 20th century. Yet there is ample opportunity for disaffected citizens and their mass movements to consciously remove the constraints of hyper-individualism and bring collective action forward to a second heyday.

Sources

[1] Saleh, Bailey. “Humanist Capitalism: An Alternative Ideology for the 21st Century.” Quest Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science. August 16th, 2021. https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol9-issue2/Ser-3/C09020816.pdf

[2] Buckley, Ross. “Re-Envisioning Economic Sovereignity: Developing Countries and the International Monetary Fund.” University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series. 2007. https://law.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1026&context=unswwps-flrps#:~:text=The%20Role%20and%20Impact%20of,or%20technical%20assistance%20from%20the.

[3] Han, Byung-Chul. “Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power.” Verso Books. January 1st, 2014. https://www.versobooks.com/products/226-psychopolitics?srsltid=AfmBOoqL8otpNNerC-d1I6CiPtCtPeghMsZfnrNq58NJApS1RQY9SsW0.

[4] Meeker, Katie. “A Student’s Guide to Selling Your Soul.” The Commonwealth Times. September 3rd, 2025. https://commonwealthtimes.org/2025/09/03/a-students-guide-to-selling-your-soul/.

[5] Hasan, Abul. “Jihad of Palestine: Shaikh Sudais’s Theory of Fitna and the Consequences of Ulama’s Closeness to Rulers.” The Monthly Alkawsar. December 2023. https://www.alkawsar.com/en/article/3512/.

[6] Vision of Humanity Editorial Staff. “Civil Unrest in the World Has Doubled in Past Decade.” Vision of Humanity. October 8th, 2020. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/civil-unrest-on-the-rise.

[7] Vision of Humanity Editorial Staff. “The Rise and Spread of Gen Z Protests.” Vision of Humanity. October 1st, 2025. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/the-rise-and-spread-of-gen-z-protests/.

[8] Madagascar Tribune Staff. “A radioscopy of a fragmented country: between elites and the people”. Madagascar Tribune. September 13th, 2025. https://www.madagascar-tribune.com/Radioscopie-d-un-pays-fragmente.html.

[9] Randriamanga, Tslaviny. “Manifestation of Gen-Z: The Movement in Search of Direction.” L’Express De Madagascar. October 10th, 2025. https://www.lexpress.mg/2025/10/manifestation-de-la-gen-z-le-mouvement.html.

[10] Rashiduzzaman, M. “An Ideological Rebranding?” New Age. December 23rd, 2024. https://www.newagebd.net/post/opinion/253487/an-ideological-rebranding.

[11] Jahangir, Abdur Rahman. “Thousands March in Bangladesh Calling for Prosecution of Overthrown PM.” AP. December 31st, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/bangladesh-hasina-student-protests-353ca862e4343779a8c420507d93c28a.

[12] Rashiduzzaman, M. “An ideological Rebranding?”

[13] Singh, Nikil Pal. “Zohran’s Promise.” Dissent Magazine. November 5th, 2025. https://dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/zohrans-promise/.

[14] Goldberg, Emma, and Oreskes, Benjamin. “Mamdani’s Mayoral Run Gave Gen-Z More Than Politics”. New York Times. November 4th, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/04/nyregion/mamdani-young-voters.html.

[15] Oppenheimer, Robert. “Oppenheimer’s Farewell Speech.” Nuclear Museum. November 2nd, 1945. https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/key-documents/oppenheimers-farewell-speech/.

[16] Palme Dutt, Rajani. “Fascism and Social Revolution.” International Publishers. 1943. https://www.marxists.org/archive//dutt/1935/fascism-social-revolution-3.pdf.

[17] Eisenhower, Dwight D. “President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Farewell Address (1961).” National Archives. January 17th, 1961. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/president-dwight-d-eisenhowers-farewell-address.

[18] Getty, John Arch. “Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933–1938.” Cambridge University Press. April 26th, 1985. https://archive.org/details/originsofgreatpu0000gett_z5x5.

[19] Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich. “What Is To Be Done: Burning Questions of Our Movement.” 1901. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/index.htm.

[20] Michael Brenes and Daniel Steinmetz Jenkins. “The Legacies of Cold War Liberalism.” Dissent Magazine. 2021. https://dissentmagazine.org/article/legacies-of-cold-war-liberalism/.

[21] Lively, Sophie. “Hyper-Individualistic and Focused on Worth, the Manosphere is a Product of Neoliberalism.” The Conversation. April 24th, 2025. https://theconversation.com/hyper-individualistic-and-focused-on-worth-the-manosphere-is-a-product-of-neoliberalism-254339.

[22] Henry C. Santos, Michael E. W. Varnum, and Igor Grossman. “Global Increases in Individualism.” Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617700622.

[23] Nye, Joseph S., Jr. “Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics.” PublicAffairs Books. 2004. https://www.wcfia.harvard.edu/publications/soft-power-means-success-world-politics.

[24] Alexeivich, Svetlana. “Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets.” Penguin Random House. 2013. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/541184/secondhand-time-by-svetlana-alexievich/.

[25] Realist News Agency Staff. “United Russia is ‘Putin’s Party’ and Cannot Have an Ideology.” Realist News Agency. December 6th, 2021. https://realtribune.ru/edinaya-rossiya-partiya-putina-u-nee-ne-mozhet-byt-ideologii/.

[26] Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History and the Last Man.” The Free Press. 1992. https://ia803100.us.archive.org/33/items/THEENDOFHISTORYFUKUYAMA/THE%20END%20OF%20HISTORY%20-%20FUKUYAMA.pdf.

[27] Fukuyama. “The End of History and the Last Man.”