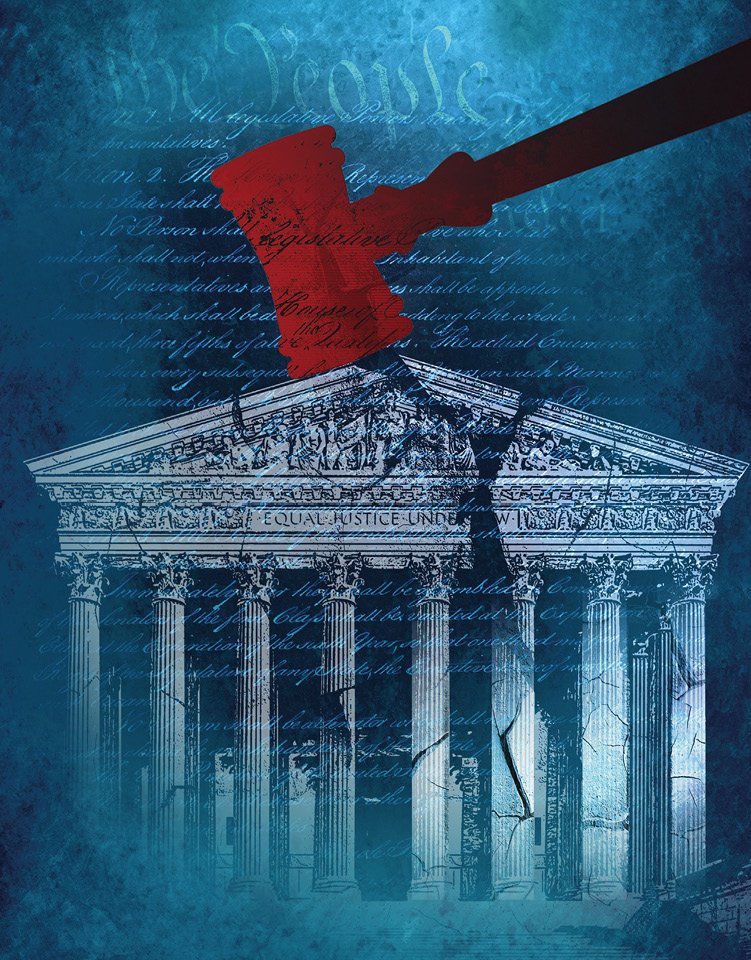

Judicial Supremacy: A Threat to Democracy?

One would think that the highest court in the land can be relied upon, but with 44% of Americans having an unfavorable opinion of the Supreme Court, it is clear that the court has lost the public’s trust. Judicial supremacy, set into motion by Marbury v. Madison (1803) and solidified by Cooper v. Aaron (1958), is the precedent that the Supreme Court’s rulings are the ultimate interpretations of the constitutions and are binding, thus making it imperative that justices are unbiased and not allied to any one interest group or party. Yet, what appears to be a central tenement of the American justice system has become more and more controversial as the ideologies of the court have evolved and contentious decisions are released each June. Most recently, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed a woman’s right to an abortion under the 14th Amendment, has sparked national outcry and reinvigorated debates regarding what degree of power the Supreme Court should have. With the advent of presidential appointments being used to formulate policy in the 1960s, the Court’s absolutist control over the laws of the land presents a dangerous structure in which the citizens of the United States, and the congressmen that represent them, are losing their voice in politics, forced to abdicate their influence to the nine justices that sit on the Supreme Court for life-long terms. Judicial Supremacy has allowed for Supreme Court appointments to be taken advantage of as a political tool, resulting in rulings that have historically restricted the rights of the American people and do not represent the will of the public. This newfound tug-of-war battle for control of the court by both sides of the political spectrum poses a threat to democracy and the faith we have in our institutions.

Scholars gauge the court’s politicization to have occurred in response to the liberal decisions of the Warren Court, as President Reagan realized the power of presidential appointments to the court and utilized it to further his policy goals. Stephen M. Griffin, author of Judicial Supremacy and the Equal Protection of Rights, traces the origins of the court’s politicization to the Civil Rights Era, which in turn prepared the nation for a conservative response. The Supreme Court under Earl Warren garnered a reputation for uplifting racial minorities and expanding civil rights and court influence. Griffin points out that prior to this time period, Court appointments were of little importance to politicians, but the Court’s ability to set a national agenda caused even presidents to take notice. The evidence of its politicization can be found in President Reagan’s task force whose sole purpose centered around anticipating Supreme Court vacancies and having vetted candidates ready in the event of one. The twelve factors the task force took into account included “respect for traditional values” and “refusal to create new constitutional rights for the individual.” These requirements to be a Supreme Court candidate in the eyes of Reagan illustrate a political goal he was attempting to impose via the Court. The recognition of this power spurred future majorities to place their own representatives on the Court to counteract the decisions delivered that were not in their best interest. The power and politicization of presidential appointment, beginning its exploitation in the 1960s, is felt well into today. In 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell denied President Obama’s nomination to the Supreme Court by arguing, “all we are doing is following the long-standing tradition of not fulfilling a nomination in the middle of a presidential year.” However, just four years later, Amy Coney Barrett was nominated by President Trump and confirmed by the Senate to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg a mere week before Election Day. This decision to appoint a Justice depending on whether or not Congress or the Presidency is controlled by a certain political party shows the political ways that Justices are appointed. If Supreme Court Justices were truly as independent as alleged to be, this battle for Supreme Court seats would not occur.

The Supreme Court has been described as “monarchical” by scholars due to the ways in which it fails to truly represent the will of the American people. Just nine unelected justices are supposed to make decisions on behalf of an entire citizenry. Congress, an elected body representing constituents from every corner of the nation, can only undo the binding decisions of the Supreme Court through a vote of a two-thirds majority (by passing a constitutional amendment). Supreme Court Justices may have even been chosen by Presidents who arguably were not selected by the will of the people if the President lost the popular vote. Brandon J. Murrill points out that judicial supremacy can entail “unelected judges overturning the will of a democratically elected branch of the federal government or popularly elected state officials” and instead may be deciding cases based on personal political preferences. An example of a case in which this may be what occurred is City of Boerne v. Flores. In 1997, the Supreme Court decided to override the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which had been passed by Congress in 1993, citing its ability to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process and Equal Protection clauses. The Court came forward stating that Congress does not possess the power to interpret the Fourteenth Amendment, only the Supreme Court does. This decision was a massive assertion of judicial supremacy, protecting their own power at the expense of civil rights. Thus, a doctrine was created that restricts the ability of Congress to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. Despite the elected members of Congress being able to pass an Act with substantial support, the undemocratically selected Supreme Court Justices were able to strike it down in order to preserve their own political influence. Not only can politicization and a desire to preserve power interfere with Court rulings, but the unique methods applied by each Justice when interpreting the constitution can as well.

Murrill details the different approaches to interpreting the constitution and how it can allow for bias to invade decision-making. The eight most common strategies Justices apply are known as textualism, original meaning, judicial precedent, pragmatism, moral reasoning, national identity, structuralism, and historical practices. Textualism appears to not allow room for bias, as it centers on the plain meaning of the text itself. However, opponents argue that the meaning of the text can be interpreted according to a Justice’s beliefs or background. Original meaning, otherwise known as originalism, holds that the Constitution should only be interpreted to mean what the authors had in mind in 1788. This fails to account for changes in modern society and does not represent the modern American people properly. Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett are self-proclaimed originalists, making decisions for 21st-century citizens based on 18th-century ideals. Pragmatism also presents an opportunity for politicization to take root, as it calls for weighing the circumstances of the political and economic contexts of the nation, directly requiring Justices to make a decision based on a certain policy or political view. The practice of moral reasoning is also prone to a Justice’s personal opinion, as it allows one to determine what is ethical or not which is substantially determined by a Justice’s political views. Although some Justices ascribe to a multitude of interpretation modes and do not restrict themselves to one, the avenues for politicization are very much present even where one might not expect them to be. In choosing one method and not deviating from it, Judges inherently introduce bias into their practice—perhaps not personal political bias, but bias based on the specific method they use. Interpreting the constitution is not an exact science, and yet the structure of the United States government entrusts nine people to do it and to determine what laws will govern 332 million people. This process of utilizing modes of interpretation shows just how subjective the Supreme Court is. How can the people of the United States trust these Justices are making the correct decisions for the nation based on the narrow perspective they apply to the constitution? How can it be expected that these few common interpretation modes will cover everything that should be taken into account when deciding what is constitutional or not?

Newly uncovered power in setting national agenda via Presidential nominations in conjunction with bias interfering with modes of interpreting the constitution has caused the Supreme Court to be set upon a path of politicization. Presidents are able to tactically nominate Justices who ascribe to their beliefs to the Court, who are subject to personal views interfering with rulings. Titles have been given to Justices, calling them “conservative” or “liberal” which should not matter in the theory of the Supreme Court being just and nonpartisan. It is no secret that Democrats and Republicans compete for influence through the Supreme Court, as Presidents from the respective parties seek out justices who will make decisions they agree with. The only way this is possible is if the very nature of the structure of the Supreme Court even allows a Justice’s personal beliefs to shine through. The Court takes power away from the legislative branch, deciding what laws can or cannot be made and going as far as to overturn already decided Congressional actions. Nine justices, each with their own backgrounds and personal beliefs, are able to decide for the country what civil rights they are entitled to and strike down decisions from other branches of government they do not agree with. The Supreme Court is far too powerful in its governance of the nation, and checks and balances are failing to contain its hegemony. It has become a political pawn of Presidents and their parties, weaponized to enact or tear down policies, and it can not be trusted to deliver rulings on behalf of the people. An unelected institution being so influential goes against the foundation of democracy. “Rule by the people” looks a lot like “rule of the people” when the people have no say in what is being decided and no say in who is deciding. Judicial supremacy—a status quo not present in the constitution—is an outdated and dangerous tenement of the judicial branch.

Sources

1. Lemieux, Scott E. “Judicial Supremacy, Judicial Power, and the Finality of Constitutional Rulings: Perspectives on Politics.” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, 18 Sept. 2017, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/judicial-supremacy-judicial-power-and-the-finality-of-constitutional-rulings/D3EDFCDBAC9AF88AC38E4BEDE32643C2.

2. Stephen M. Griffin, Judicial Supremacy and Equal Protection in a Democracy of Rights, 4 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 281 (2002.)

3. Murrill, Brandon J. “Modes of Constitutional Interpretation.” Congressional Research Service. 2018.

4. Nadeem, Reem. “Public's Views of Supreme Court Turned More Negative Before News of Breyer's Retirement.” Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy, Pew Research Center, 7 Feb. 2022, www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/02/02/publics-views-of-supreme-court-turned-more-negative-before-news-of-breyers-retirement/.

5. Rappaport, Mike. "The Year in Originalism – Mike Rappaport." Law & Liberty. March 16, 2021. https://lawliberty.org/the-year-in-originalism/.

6. Sprunt, Barbara. “Amy Coney Barrett Confirmed To Supreme Court, Takes Constitutional Oath.” NPR, NPR, 27 Oct. 2020, www.npr.org/2020/10/26/927640619/senate-confirms-amy-coney-barrett-to-the-supreme-court.

7. Wheeler, Russell. “McConnell's Fabricated History to Justify a 2020 Supreme Court Vote.” Brookings, Brookings, 9 Mar. 2022, www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/09/24/mcconnells-fabricated-history-to-justify-a-2020-supreme-court-vote/.