How Iran is Reshaping the Sudanese Civil War

The ongoing Sudanese civil war has caused one of this decade’s worst humanitarian crises. Millions of civilians have been caught in the crossfire between two warring factions, and indiscriminate violence has displaced over 11 million people [1]. In Darfur, the Rapid Support Forces (R.S.F.) have been accused of systematically targeting Black non-Arab residents, raising fears of genocide. Meanwhile, the Sudanese Armed Forces (S.A.F.) have conducted devastating airstrikes on urban areas, endangering civilian lives and cutting off access to basic necessities. The death toll has already reached 20,000, with no end in sight [2].

Despite this severe crisis, international powers have turned Sudan’s internal struggle into a regional power play. The S.A.F. is supported by Egypt, the United States, Turkey, and Iran, each pursuing interests like regional stability or strategic alliances [3]. On the opposing side, the R.S.F. leverages its control over Western Sudan’s gold mines to gain support from the UAE, Russia, the Libyan National Army, and Chad. These powers seek to exploit Sudan’s natural resources for their own economic interests—from arms funding to sanctions evasion [4]. Gold is a near-universally accepted currency that helps Russia bypass the Western financial system, and uphold their currency. The involvement of external actors has turned Sudan’s civil war into a high-stakes proxy conflict, with each alliance seeking influence in a strategically important, resource-rich region.

Yet, among Sudan’s foreign backers, Iran’s involvement raises questions. Despite a historic rivalry with the United States, Iran is supporting the S.A.F. with strategic training, drones, and advanced weaponry [5]. This backing has been game-changing, enabling the S.A.F. to reclaim several strategic areas including parts of Khartoum. Tehran’s actions raise questions about its motivations, particularly as its support has shifted the balance of power in this conflict.

This article analyzes Iran’s role in Sudan’s civil war through four critical lenses. First, it examines the historical ties between Iran and Sudan, particularly the S.A.F.’s connections to Islamist factions from the Bashir era, and how these ties have persisted till today. Second, it assesses the effectiveness of Iranian weaponry and support in Sudan, analyzing key victories attributed to Iranian technology and military tactics. Third, it investigates why Iran’s support has been particularly game-changing, focusing on Iran’s modern history and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (I.R.G.C.). Finally, it considers the broader implications of Iran’s involvement for Sudan’s future, regional stability in Africa, and U.S. interests in countering Iran’s expanding influence in the area.

Iran-Sudan Relations: A History

In 1989, Omar Al-Bashir came to power in Sudan through a military coup, establishing a regime hostile to Western influence. From 1990 to 2014, Sudan and Iran forged a strong alliance based on shared political and ideological goals. Al-Bashir’s government, under the National Islamic Front (later the National Congress Party), sought to "Islamize" Sudan’s political structure, aligning closely with Iran’s vision of a region resistant to Western influence [6]. Since 1979, Iran has been ruled by an Islamic fundamentalist regime with a strong revisionist vision for the Muslim world. Therefore, Iran supported Bashir’s government, supplying Sudan with approximately one million tons of oil annually, along with significant military aid [7]. Al-Bashir’s government also hosted groups like Al-Qaeda and supported Saddam Hussein during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. In 1993 the United States designated Sudan as a “rogue state” and a state sponsor of terrorism due to its radical foreign policy. Bashir’s regime also sought to mobilize various popular militias that were loyal to the regime, such as the R.S.F. The Popular Defense Forces (P.D.F.) is another such example that has often been overlooked. Aligned with the National Islamic Front, the PDF was mobilized to enforce Bashir’s version of political Islam and suppress non-muslim separatists in South Sudan [8].

Tehran deepened its influence in Sudan by providing Bashir’s government with continued military and political support throughout the early 2000s. The Darfur genocide in 2003 and the secession of South Sudan in 2011 did little to weaken the partnership [9]. By 2012, Sudan was Iran’s strongest ally in Africa [10]. Despite growing international pressure on Al-Bashir’s regime, the bond between the two nations remained steadfast.

However, the partnership between Sudan and Iran collapsed abruptly in 2015 when Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir expelled Iranian diplomats and joined the Saudi-led coalition against the Houthis in Yemen [11]. This shift was due to Khartoum’s urgent need for financial aid, as Sudan’s economy was struggling following decades of sanctions, corruption, and conflict. Al-Bashir’s pivot to Saudi Arabia temporarily ended Sudan’s alliance with Iran, as Khartoum sought closer ties with the Gulf nations. Facing growing unrest and fear of an uprising, Al-Bashir strategically shifted to align with the Gulf states, especially Saudi Arabia, which promised crucial economic support [12]. This pivotal realignment proved lucrative, as Sudan received over $2.2 billion in financial aid.

In 2019, a popular uprising ended Al-Bashir’s three-decade-long rule, creating a power vacuum and introducing a transitional government with a democratic mandate. For Tehran, this development offered little prospect for Iranian influence in Sudan, as the new transitional government pursued closer ties with Western countries, including the U.S. and Israel [13].

The Popular Defense Forces (P.D.F.) militia group remained an opaque faction within Sudan’s military landscape. While the S.A.F. officially claims that the P.D.F. was disbanded after the coup, other reports suggest that the militia was absorbed into the S.A.F. [14]. In this scenario, the PDF could exert significant influence on the S.A.F.’s ideological leanings, positioning them as a potential source of support for pro-Iran factions.

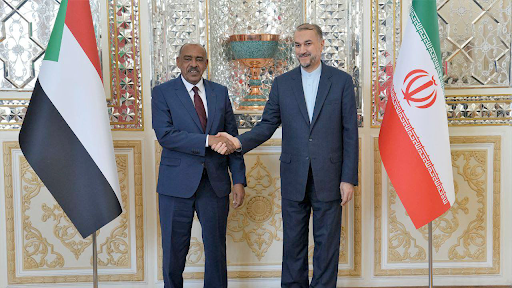

In 2021, the S.A.F. orchestrated another coup, disbanding the transitional government that had been in place since the 2019 coup, and postponing elections. This decision severely reduced the R.S.F.’s influence within the government and led to significant tensions with the R.S.F. These tensions would eventually escalate into the ongoing Sudanese Civil War, which started on April 15th, 2023. By July, the S.A.F., facing weakening support and poor performance, re-established ties with Iran. Neither side could have predicted how influential this decision would be.

The Effectiveness of Iranian Support

By providing advanced weaponry, particularly drones and anti-tank missiles, Iran has significantly enhanced the capabilities of the S.A.F. in the ongoing civil war [15]. The Mohajer-6 drones, renowned for their durability and low cost, have proven crucial in S.A.F.’s counter-offensives, particularly in reclaiming areas of strategic importance such as the capital, Khartoum. Equipped with precision targeting, these drones enable S.A.F. forces to strike R.S.F. positions accurately, reducing the need for extensive ground operations [16]. For example, if an R.S.F. unit is entrenched in a multi-story building in a dense neighborhood of Khartoum, conventional forces would have to storm it from the ground up — a tactic that is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and incredibly dangerous. Using precision drones, the S.A.F. can target an exact room or floor from the air, minimizing civilian and military casualties.

In addition to drones, Iran’s Saeghe anti-tank missiles and armored vehicles have been instrumental in overcoming R.S.F. defenses, especially in contested areas like Omdurman [17]. These anti-tank missiles, known for their ability to penetrate heavy armor, have allowed S.A.F. to neutralize Emirati-supplied armored vehicles used by R.S.F. forces [18]. This support from Iran has transformed S.A.F.’s battlefield tactics, enabling them to launch targeted, efficient strikes against R.S.F. positions. These capabilities, coupled with S.A.F.’s existing artillery and airpower, provide them a highly effective approach to overcome R.S.F. forces, who rely heavily on lighter arms and mobile units.

Why is Iran Effective?

Iran’s support is particularly effective due to the history of Iran’s I.R.G.C., which was founded in 1979 to defend Iran’s post-revolution government. The I.R.G.C. built its unique military doctrine around guerrilla and asymmetrical warfare, diverging sharply from the conventional warfare tactics of Western militaries [19]. Typical Western military doctrines focus on large-scale operations, developing the most advanced technology, and seeking overwhelming firepower. In this respect, most Western militaries outclass Iran’s Artesh (conventional Iranian military). In contrast, guerrilla tactics prioritize small, highly mobile units, hit-and-run attacks, and exploiting the enemy’s weaknesses over direct confrontation, making them effective against larger, better-equipped conventional forces.

Insurgent warfare exposes the limitations of conventional military approaches. Western militaries often face challenges in armed conflicts against guerrilla and insurgent forces. For example, Egypt’s decade-long struggle to defeat ISIS in the Sinai, Israel’s repeated failure to eliminate Hezbollah and Palestinian militant groups, Saudi Arabia’s failed drone war against the Houthis, as well as the U.S. and Soviet Union’s numerous failures in Afghanistan. All of these examples underscore how conventional tactics often fall short in guerilla wars.

By contrast, Iran’s success with asymmetrical warfare can be traced back to decades of involvement in conflict zones, including Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. This experience has honed the I.R.G.C.’s ability to train allied forces in guerilla tactics that prioritize mobility, adaptability, and resourcefulness over heavy firepower. It is evident that the I.R.G.C.’s support has enabled the S.A.F. to adopt similar guerrilla tactics, enabling them to effectively counter the R.S.F. and reclaim critical areas like Khartoum.

Implications

For Sudan:

The prospect of an S.A.F. victory, with ongoing support from Iran, raises the likelihood of entrenched Iranian influence in Sudan. Discussions of establishing an Iranian naval base in Sudan highlight this possibility. A stable alliance with S.A.F. would provide Iran with direct access to the Red Sea—a critical strategic advantage for projecting power in East Africa [20]. A military victory for the S.A.F., particularly one supported by Iranian weaponry, would almost certainly cement Iran’s influence over Sudanese military and foreign policy. In the best-case scenario, Sudan would serve as a reliable Iranian ally, aligning its foreign policy to further Tehran’s interests.

However, in a worst-case scenario, Sudan could mirror Syria’s trajectory under Bashar al-Assad. Isolated by the international community in 2006, the Assad regime established a strong relationship with Iran [21]. Iran subsequently played a crucial role in Assad’s retention of power, deploying troops and militias to violently suppress anti-regime protests and crush democratic movements. The Iranian intervention was marked by brutal tactics, with civilian populations often caught in the crossfire, creating a lasting humanitarian catastrophe. If Sudan falls further under Iranian influence, there is potential for a similar outcome: Iran bolsters an authoritarian regime to crush domestic unrest, to the detriment of the Sudanese people.

For Africa:

The success of Iranian-backed counterinsurgency tactics in Sudan highlights a potential shift in the future of counterinsurgency tactics, especially in Africa, where conventional militaries have struggled against insurgent groups [22]. Iran’s I.R.G.C. has a proven record of success in asymmetrical warfare. As the S.A.F. delivers tangible successes with Iranian military support, other countries in the region grappling with insurgencies may start looking towards Iran as an alternative military partner. Countries like Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Somalia, where insurgencies are rampant and conventional forces have been largely ineffective, may begin to view Iranian support as a viable option for countering militant threats and restoring stability.

Expanding its military cooperation would allow Iran to extend its “Axis of Resistance” deep into the African continent, directly challenging established powers such as France, the United States, and Russia, which have historically served as security partners in the region [23]. This shift would mark a future where asymmetrical warfare specialists, such as Iran, India, Türkiye, and Pakistan, hold greater influence than conventional warfare specialists, particularly in countries affected by insurgencies. As Iran’s support to the S.A.F. reshapes the conflict in Sudan, it offers a case study of how alternative military strategies and partners could shape counterinsurgency efforts worldwide.

For the U.S.:

To counter Iran’s expanding influence in Sudan and beyond, the U.S. must consider adopting a more active role in supporting the S.A.F. to counter Iranian influence. By providing enhanced logistical, intelligence, and tactical support to the S.A.F., the U.S. can reinforce its position within the Sudanese conflict and prevent Iranian dominance in a region already plagued by extremism.

Beyond Sudan, the U.S. faces a broader challenge across West Africa, where escalating insurgencies in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have left them increasingly vulnerable to foreign influence [24]. Mending and strengthening diplomatic and security ties with these nations is essential to countering Iran’s entry into African geopolitics while also addressing the region’s security and stability needs.

Moreover, as asymmetrical and insurgency-driven conflicts continue to shape global security problems, the U.S. military must place greater emphasis on counterinsurgency tactics, which are increasingly vital in conflicts where traditional warfare falls short. The U.S. may benefit from refining its counterinsurgency training, drawing lessons from Iran’s success in this region, and adapting its methods to better handle unconventional warfare. Developing a nuanced counterinsurgency approach could also prevent a repeat of Afghanistan’s pitfalls, allowing the U.S. to operate more effectively in complex environments and compete with nations like Iran that have leveraged their expertise in asymmetrical warfare to project influence across regions.

Conclusion

Iran's role in Sudan’s civil war extends beyond simple support for the S.A.F. By providing advanced weaponry, tactical expertise, and strategic backing, Iran has elevated the S.A.F.'s asymmetrical warfare capabilities, shifting the balance of power against the R.S.F. This deepening involvement establishes Iran as a significant force not only in Sudan but potentially across Africa, where insurgencies often outmaneuver traditional military forces. For the U.S. and other global powers, Iran’s growing footprint signals a need to reevaluate and adapt counterinsurgency tactics to face the complex nature of modern conflicts, particularly in regions susceptible to insurgent influence. Underestimating Iran’s impact would be a mistake; the real threat to U.S. hegemony may not come from apparent actors like Russia or China, but from failing to adapt to asymmetrical warfare and allowing countries like Iran to slip under the radar.

Sources

[1] Council on Foreign Relations. "Power Struggle in Sudan." Global Conflict Tracker, November 17, 2024. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/power-struggle-sudan.

[2] Pospisil, Jan. "Sudan Civil War Stretches into a Second Year with No End in Sight." PeaceRep, April 24th, 2024. https://peacerep.org/2024/04/24/sudan-civil-war-stretches-into-a-second-year-with-no-end-in-sight.

[3] Amin, Mohammed, and Oscar Rickett. "What is the Future of the Sudanese Armed Forces?" Middle East Eye, April 4th, 2024. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/sudan-crisis-SAF-army-future.

[4] Young, Alden. "How Sudan’s Wars of Succession Shape the Current Conflict." Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 3rd, 2024. https://www.fpri.org/article/2024/07/how-sudans-wars-of-succession-shape-the-current-conflict.

[5] Sons, Sebastian. "New (Old) Player in Town? Sudan-Iran Reconciliation and Its Regional Implications." Brussels International Center for Research and Human Rights, September 5th, 2024. https://bic-rhr.com/research/new-old-player-town-sudan-iran-reconciliation-and-its-regional-implications.

[6] Kostelyanets, Sergey. "The Rise and Fall of Political Islam in Sudan." Politikologija Religije 15, January 2021. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=950079.

[7] Schanzer, Jonathan. "A Deadly Love Triangle." The Weekly Standard, August 6th, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20120309165657/http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/401vcvba.asp.

[8] Young, John. The Paramilitary Revolution: The Rise of Complex Militias and Paramilitary Groups in Sudan, December 2007. https://smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/HSBA-WP-10-Paramilitary-Revolution.pdf.

[9] Tubiana, Jerome. "Darfur after Bashir: Implications for Sudan’s Transition and Region." United States Institute of Peace, April 20th, 2022. https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/04/darfur-after-bashir-implications-sudans-transition-and-region.

[10] Schanzer, Jonathan. "A Deadly Love Triangle." The Weekly Standard, August 6th, 2008.

[11] Abdelaziz, Khaled. "Sudan Expels Iranian Diplomats, Closes Cultural Centres." The Guardian, September 2nd, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/02/sudan-expels-iranian-diplomats-closes-cultural-centres.

[12] Al-Monitor Staff. "Sudan Joins Saudi Arabia’s War in Yemen." Al-Monitor, November 2015. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/11/sudan-saudi-arabia-war-yemen-houthi-economy.html.

[13] Zaidan, Yasir. "Sudan-Israel Diplomatic Relations: Netanyahu and Al-Burhan Meeting." Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, October 10th, 2020. https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/israel-hebrew/sudan-israel-normalization-diplomatic-relations-netanyahu-al-burhan.

[14] Dabanga Sudan Staff. "Sudan Armed Forces: Popular Defense Forces Dissolved, Not Absorbed." Dabanga Sudan, September 6th, 2020. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/sudan-armed-forces-popular-defence-forces-dissolved-not-absorbed.

[15] Stratfor Staff. "Why Is Iran Sending Drones to Sudan’s Armed Forces?" Worldview by Stratfor, August 23rd, 2023. https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/why-iran-sending-drones-sudanese-armed-forces.

[16] Taylor, Edwin. "Iran-Sudan Relations: Drone Supply and Red Sea Access." Grey Dynamics, August 28th, 2024. https://greydynamics.com/iran-sudan-relations-drone-supply-red-sea-access.

[17] Abdul, Kazim. "Iranian Anti-Tank Missile Systems on Sudan’s Battlefield." Military Africa, May 12th, 2024. https://www.military.africa/2024/05/iranian-anti-tank-missile-system-flood-sudans-battlefield.

[18] ADF Staff. "Drones Supplied by Iran and UAE Threaten to Prolong Sudan Conflict." ADF Magazine, July 9th, 2024. https://adf-magazine.com/2024/07/drones-supplied-by-iran-and-uae-threaten-to-prolong-the-conflict-in-sudan.

[19] Connell, Michael. "Iran’s Military Doctrine." The Iran Primer, United States Institute of Peace, October 11th, 2010. https://iranprimer.usip.org/sites/default/files/Iran_s%20Military%20Doctrine.pdf.

[20] Taylor, Edwin. "Iran-Sudan Relations." Grey Dynamics, August 28, 2024.

[21] Wastnidge, William. "Iran and Syria: An Enduring Axis." Asian Affairs, June 19th, 2017. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/MEPO.12275

[22] Cooke, Jennifer and Sanderson, Thomas. "Militancy and the Arc of Instability in the Sahel." Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), September 2016. https://www.csis.org/programs/former-programs/transnational-threats-project-archive/militancy-and-arc-instability-2-0.

[23] Reuters Staff. "What Is Iran’s ‘Axis of Resistance’?" Reuters, January 29th, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/what-is-irans-axis-resistance-which-groups-are-involved-2024-01-29.

[24] African Center for Strategic Studies. "Militant Islamist Groups Advancing in Mali." Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 24th, 2024. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/militant-islamist-groups-advancing-mali/.