Gen-Z Swings Towards Intervention

Today’s college Tik-Tokers are going to be tomorrow’s world leaders. Our response to future international conflict will be dramatically affected by the invasion of Iraq, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and other political events experienced by Millenials and Gen-Z in late adolescence. The impacts of these conflicts on our generation will set the stage for how we remedy Chinese aggression.

It is widely accepted that adolescent experiences have a profound impact on our development and worldview into adulthood. An extensive body of scholarship has established the impact of family relationships, friendships, and cultural events on shaping adolescents’ moral reasoning, identity, and overall understanding of the social world [1][2]. But many events are not experienced solely by one child, they are shared by an entire generation of children. Jeffrey Arnett used this concept to argue that political events experienced in late adolescence play a significant role in shaping how an entire generation reacts once they assume positions of power [3]. Specifically, Arnett points to a period he calls “emerging adulthood,” where political beliefs are most malleable and influenced by social events: typically between the years of 18 and 25.

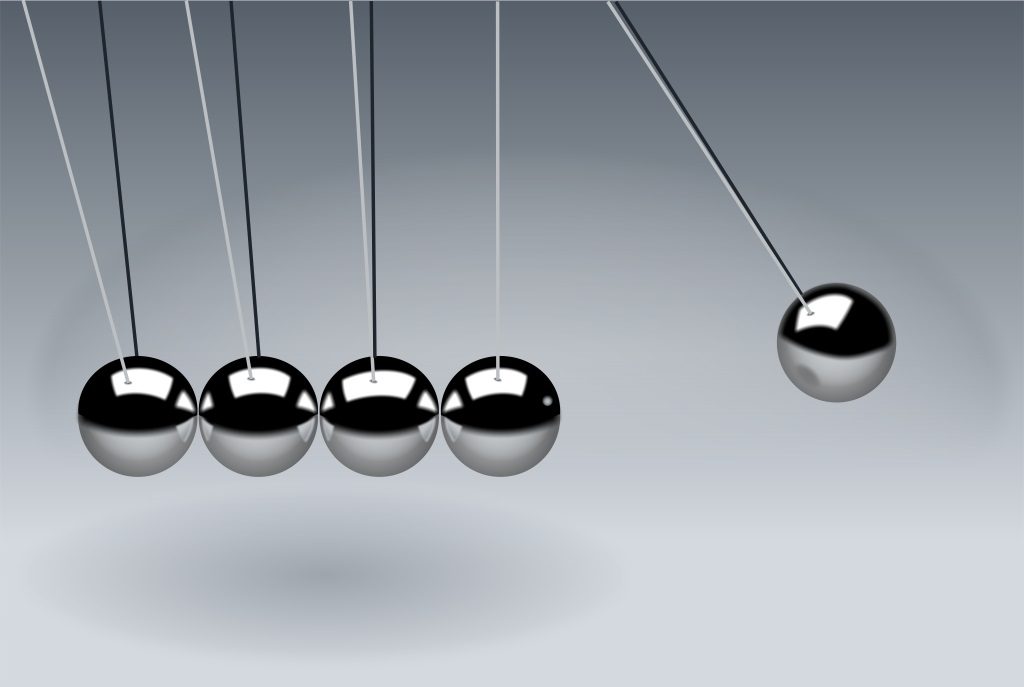

Arnett’s research is expanded by that of Michael Roskin who fifty years ago claimed generations oscillate between interventionist and isolationist paradigms caused by reactions to the failure of an existing paradigm [4]. Taken together, a framework for analyzing American responses to foreign conflicts can be developed based on the paradigms that were most influential during emerging adulthood. An example of this analysis is seen in the shifting paradigm from interventionist to isolationist during the second half of the 20th century. The success of American involvement in WWII made a generation of young people in the forties supportive of intervention. Once these adolescents were calling the shots in adulthood, they were willing to commit to interventionism in Vietnam. The failure of US intervention in Vietnam shaped a generation that was weary of foreign intervention. Thus, leaders were more isolationist. The pendulum swings from isolationism to interventionism and back again when late adolescents experience a failure of the existing paradigm.

In a 2006 column, Peter Beindart used Roskin’s rationale to hypothesize the pendulum’s direction following the Iraq War [5]. He argued the soaring cost and waning popularity of the war will cause a period of isolationism partially propelled by a generation wary of foreign intervention. Current college students are at the tail end of the generation of late adolescents affected by the failures in Iraq as perpetuated by debates in the media and between politicians. Even though many in Gen-Z were too young to remember (or born after) the early days of the Iraq War, the negative impacts are still present in modern political discourse and later elections. Many in our generation have come to see the war as a costly mistake and would be hesitant to be supportive of future military interventionism.

But the most crucial international event that will determine the direction of Gen-Z’s pendulum is undoubtedly the war in Ukraine. Though the US has not sent troops or declared war on Russia—what could be considered a lasting consequence of our post-Iraq isolationism—we have spent almost $75 billion on supplies, training, and aid for the Ukranians. Few would label this level of support as squarely isolationist. The outcome of the war in Ukraine will have a dramatic impact on how the next generation of leaders responds to foreign aggression. If the Iraq War was the conflict that shaped Millennials, Ukraine will shape Gen-Z. Roskin stresses the necessity of a policy failure to promote a pendulum swing in the opposite direction. Thus, the interventionist mindset that has prompted US support for Ukraine would have to backfire to spur a new period of isolationist sentiment.

Nevertheless, it is unlikely that Ukraine will result in a policy failure that will move the pendulum. With no US casualties, America has been able to help Ukraine fend off Russia with astonishing success. If the current interventionist paradigm faces no failure, it will show our generation that when done the right way US foreign involvement is good for the international system.

If there is potential for future US military intervention, many argue it will not be in Iraq or the Middle East, but rather China. The rise of China's geopolitical power, its increasing economic importance as a global trading partner, and its significant military advancements have contributed to the development of a fierce rivalry between the Asian superpower and the US [6][7]. The complex interplay of these factors has led to a heightened focus on the possibility of a future conflict between the two nations. Military tensions between the US allies and China have also escalated with aggressive Chinese military drills and displays of power. China has practiced extensive military operations surrounding Taiwan, effectively showing the world they have the strategy to isolate the sovereign island [8]. Just this week, a Chinese fighter jet came dangerously close to an air force jet patrolling the South China Sea, and a Chinese ship got within 150 yards of a US missile destroyer [9].

Though a security challenge with China is possible, it almost certainly will not happen in the next few years. China relies on US Navy protections, US consumers, and US companies to support the Chinese economy and is not yet in a position to directly challenge the US. When there is a hypothetical military conflict with China, it will be Gen-Z leaders determining the extent to which the US gets involved. If China invades Taiwan in ten or twenty years, leaders will look back to Iraq—and more importantly Ukraine—as evidence of the importance of US interventionism.

In discussions about growing international tensions, it is crucial to remember who will set American foreign policy and how their generation was shaped by the international events they grew up experiencing. Failures in understanding the impacts of generational influence both on others and ourselves can lead to miscalculations and impaired decision-making that relies more on feeling than rationality.

Sources

1. Smetana J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current opinion in psychology, 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012

2. Blakemore, S. J., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing?. Annual review of psychology, 65, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202

3. Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

4. Michael Roskin, From Pearl Harbor to Vietnam: Shifting Generational Paradigms and Foreign Policy, Political Science Quarterly, Volume 89, Issue 3, Fall 1974, Pages 563–588, https://doi.org/10.2307/2148454

5. Beinart, P. (2006, January 22). The isolation pendulum expect a cyclical U.S. retreat from world affairs after the Iraq War. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2006/01/22/the-isolation-pendulum-span-classbankheadexpect-a-cyclical-us-retreat-from-world-affairs-after-the-iraq-warspan/160975b3-3a88-4b56-97ad-9601997da131/

6. Allison, G. T. (2022). Destined for war: Can america and China escape Thucydides’s trap? Scribe.

7. ECONOMY, E. (2023). World according to China. POLITY PRESS.

8. Wu, H. (2023, April 11). China military “ready to fight” after drills near Taiwan. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/china-military-taiwan-us-7549c646a377f1f199d2cda983573279

9. Brown, D. (2023, June 4). Watch: New video shows Chinese warship sailing dangerously close to U.S. destroyer. POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/06/04/chinese-warship-us-destroyer-taiwan-strait-00100133