Flawed Memory and False Convictions: Eyewitness Misidentification and the Need for Reform

Imagine the last time someone bumped into you on the street. Can you remember their face? What about the color or style of their hair? Any tattoos? Piercings? Scars? Was it dark outside? Crowded? How confident are you really that you could identify them if shown pictures of others with similar features? Could you identify them with 99.9 percent confidence? Now, take that level of confidence and imagine it as one of the deciding factors in whether or not another person spends the rest of their life in prison.

It may sound dramatic to compare bumping into a stranger on the street to identifying your assailant, but the credibility of identification decreases with traumatic or stressful incidents. Although eyewitness testimony has historically been considered one of the most reliable pieces of evidence used in criminal court, research has increasingly pointed to its unreliability. The advancement of DNA technology in the last forty years brought a monumental revelation: eyewitness misidentification is one of the leading causes of wrongful convictions. The Innocence Project, a non-profit working to exonerate those who have been wrongfully convicted through DNA evidence, found that nearly 70 percent of cases overturned by new DNA evidence originally relied on eyewitness testimony [1]. Further research has shown that there are a myriad of reasons why this testimony can be so unreliable. I discussed these failings in an interview with a Georgetown Law graduate and Washington, D.C.-based public defender, who wishes to remain anonymous. She told me, “Eyewitness testimony is seen as credible because jurors assume witnesses have no reason to lie. But even honest witnesses can unintentionally misidentify someone due to the inherent flaws in human memory, and enhanced public awareness is essential to mitigate these injustices and safeguard the integrity of the judicial process.” The psychological and situational factors contributing to these errors include issues such as trauma, the weapon focus effect, cross-racial identifications, and the influence of suggestive circumstances surrounding law enforcement.

Human memory is not reliable. Stress, trauma, suggestive circumstances, race, and other external factors can reconstruct a memory and inevitably lead to misidentification [2]. As the public defender observed, “In high-stress, traumatic situations like robberies or assaults, witnesses aren’t processing information the same way they would in a calm environment. Their brains are focused on survival, not on retaining accurate details.”

Results from studies conducted by researchers at Texas A&M University show that the unreliability of human memory is highly evident in the weapon focus effect: an alteration of memory in which the presence of a weapon diverts a witness’s attention away from important details [3]. For example, someone robbed by an individual holding a gun by their hips is more likely to focus their eyesight on the gun rather than observing the individual’s features, such as tattoos, scars, or hair type.

Additionally, it has been proven that people often struggle to accurately identify those of other racial groups. Studies show that more than one-third of DNA exonerations were influenced by cross-racial misidentifications [4]. In the case of Nathan Brown, this statistic became his reality. In August of 1997, a White woman in Brown’s apartment building told police she had been assaulted by a shirtless Black man who was wearing black shorts and had a strong body odor. Police soon took Brown inside of the patrol car for a show-up identification. The woman identified him as her attacker, despite his lack of body odor. In the criminal trial, Brown testified in his own defense and alleged that he was inside his apartment taking care of his baby at the time of the attack. Four family members corroborated his alibi. However, he was convicted of aggravated rape by the Jefferson Parish Judicial District Court on November 19, 1997 and sentenced to twenty-five years in prison based on the victim’s identification alone. In June 2014, Brown was exonerated when DNA evidence provided by the district attorney’s office revealed that the real perpetrator was a seventeen-year-old Black male living a few blocks away from the apartment complex [5].

Not only is Brown’s case a testament to the failings of cross-racial identifications, but it also speaks to the dangers of law enforcement’s engagement in identification procedures. While it is necessary for law enforcement officers to be involved in these procedures, it is simultaneously crucial that their involvement not exacerbate the already suggestive circumstances surrounding identification. For example, show-up identifications, as seen in the case of Brown, are a common practice. These are often conducted shortly after an alleged crime, where police identify a suspect and ask the victim if that individual is the perpetrator [6]. According to the public defender, “Show-ups are highly suggestive. Courts recognize this, yet they remain a common practice.” In a show-up identification, suspects are often handcuffed, surrounded by police officers, and seated inside or leaning against a patrol car. These suggestive contexts, especially in the context of cross-racial identifications, can lead to errors in identifications as they imply guilt from the moment the suspect is presented to an eyewitness. When stress and trauma are factored in, an eyewitness may convince themselves that the subject before them is the correct individual simply because they feel safer knowing the perpetrator has been caught. The undue pressure on a witness to identify a suspect increases the risk of error and therefore can lead to wrongful convictions and increased danger of victims—with show-ups accounting for 30 to 77 percent of identifications [7].

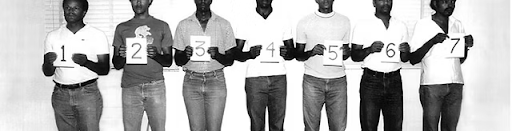

However, the solution isn’t to only eliminate the practice of show-up identifications. Other forms of identification, such as regular line-ups and photo arrays, can often be equally suggestive if mishandled. A line-up, as seen in countless movies and TV shows, is when the suspect stands in a line of others with similar features, and the eyewitness is asked to identify which individual they believe committed the crime [8]. A photo array is similar, except each person’s photograph is shown to the witness rather than an in-person identification [9]. While the aspect of extremely suggestive circumstances—such as being handcuffed and leaning on a patrol car—is absent in these procedures, there are other ways in which law enforcement can create an extremely suggestive environment [10]. For example, by failing to use adequate fillers—the other members of the lineup—the suspect can unfairly stand out and therefore be subject to biased and unfair identification. Additionally, law enforcement has intentionally and unintentionally suggestive reactions or feedback to certain individuals, which has been shown to persuade eyewitnesses into selecting the person that the officer believes is guilty [11]. For example, when an eyewitness views an image of the suspect, an officer may cough or ask if they are sure when turning over to the next image. These fallible identification methods are examples of how common eyewitness misidentification can be influenced outside of the courtroom.

The repercussions of eyewitness misidentification can be life-altering. It may lead to decades of unjust incarceration, psychological trauma, and broken families. It can ruin lives. Depression, anxiety, PTSD, and changes in self-identity are common consequences of imprisonment caused by misidentifications [12]. Social stigma and economic hardship prevail. It leaves victims in danger of their true perpetrators and ultimately leaves a scar of irreparable damage. The public defender explained, “The harm isn’t just limited to the person incarcerated—it extends to their families, their communities, and their futures.”

One example is that of Ronald Cotton, who spent over ten years in prison for a sexual assault he never committed. In July 1984, an assailant broke into Jennifer Thompson’s apartment and assaulted her. Later that night, the same assailant broke into another apartment and assaulted a second woman. Thompson testified that she memorized her assailant’s face as he assaulted her in order to identify him if she survived the attack. She was confident in her identification of Cotton, who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Ten years later, the Burlington Police Department turned over the DNA evidence to the defense. Upon testing, it revealed that the DNA was not Cotton’s and he was subsequently exonerated. Upon his release, his family and Jennifer Thompson paced in tears outside the prison for hours [13].

While there are many failures linked to eyewitness identification, this does not mean that the process should be thrown out entirely. However, it does indicate that there are systemic reforms that need to be implemented in order to prevent the imprisonment of innocent people. In my conversation with the public defender, she stressed that “We really need to look at if police departments have policies and procedures in place when conducting these identifications that account for bias and suggestive circumstances to make it as neutral a process as possible? If they don’t have those policies, they should adopt them. If they do, we have to make sure they are actually following them.”

So, what policies should be implemented? Public defenders with the Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy have discussed double-blind lineups, where the administrating officer is unaware of who the suspect is in the lineup [14]. By removing the ability for law enforcement to introduce suggestive circumstances and allude to who they believe is the suspect, the lineup’s potential for accuracy increases significantly. Sequential lineups are also a pathway toward heightened accuracy because fillers are shown subsequently rather than all at once in a group [15]. This reduces the pressure on witnesses to select someone and increases the reliability of an identification. These procedures should also be recorded so that once identifications are completed there is a clear and reviewable record. This would ensure accountability and provide an opportunity for any bias or miscarriages of the law to be monitored if there is ever a future reason to contest the witness’s identification. States like New Jersey, Colorado, and North Carolina have already made great progress in setting important precedents for reform. New Jersey [16] and North Carolina [17] both mandated double-blind lineups, while Colorado expanded post-conviction DNA testing [18]. Although these endeavors are hopeful, there is still much more work to be done.

Reforms are vital, but none will be effective without increased education—especially among jurors—of the unreliability of eyewitness testimony, which is often underestimated. In my conversation with the public defender, she told me, “Jurors want to believe eyewitnesses because they seem credible. They don’t realize how easily memory can be influenced or distorted.” Not only do we need systemic and structural reforms, but also a societal shift towards questioning the reliability of identifications. When the consequences of misidentification are so detrimental, it is crucial that we do all that we can to prevent them. The defense attorney concluded with, “The ultimate goal should be ensuring the right person is held accountable. To achieve that, we must stop relying so heavily on a form of evidence that is so deeply flawed.” By implementing reforms and educating the public, we can ensure the delivery of equitable justice in our criminal legal system.

Eyewitness Misidentification with a D.C. Public Defender

Note: The views expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bruin Political Review.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): Can you tell me about your background and what led you to become a public defender?

D.C. Public Defender: After I graduated college I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a lawyer or not. I got a job working at a law firm in their pro-bono department to test the waters and see if law was something I was interested in. That law firm did a lot of criminal defense work in the pro-bono space–things like death penalty appeals, Innocence Project cases, civil rights cases on behalf of inmates in prisons. From all of that I saw a whole different side of the criminal legal system that I never really had to confront before. It was very eye opening to see how the legal system at every single step subjugates and suppresses communities of color; how indigent folks can’t afford the representation that they need and how opportunities for post-conviction avenues are really cut off for people. It was very eye opening. It changed my perspective dramatically–not just about the legal system, but our society generally. From that point I knew I wanted to be a public defender and an advocate for the people and the communities that are so often targeted, disadvantaged, and oppressed by the criminal legal system.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): That’s really interesting. It’s great that you mentioned the Innocence Project, because I’d like to talk about their work concerning eyewitness misidentification. From your experience, how common is eyewitness misidentification in criminal cases?

D.C. Public Defender: How common it is really depends on the type of case we are talking about. I say that because in my experience of being in this work, eyewitness misidentification is most common in cases that involve strangers. For example, if we’re talking about a domestic violence complaint where the two parties know each other, that’s not a situation where you’re talking about eyewitness misidentification, most of the time. In a lot of gun or drug possession cases, what we’re seeing more of is police actively surveilling people and a heavy use of body worn camera and surveillance footage. So, misidentification becomes less common in that setting–at least in most major cities because of the level of police surveillance.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): When it comes to law enforcement, how much of a role do you think that plays in eyewitness misidentifications?

D.C. Public Defender: Do you mean in terms of how they engage in identification procedures?

Bruin Political Review (BPR): Yes.

D.C. Public Defender: I think law enforcement and how they handle identification procedures probably plays a bigger role than most people would realize. It’s because we as a society generally underappreciate the suggestivity that comes along, purely by the fact that law enforcement is involved. Any interaction with law enforcement is going to be a suggestive environment.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): Aside from law enforcement’s direct involvement, what are some main factors that could lead to misidentification?

D.C. Public Defender: You have to think about the nature of the interaction between the complainant and the suspect in the given situation. It’s probably a high stress and traumatic situation. A robbery, burglary, or an assault. Those are situations that often catch people by surprise. They happen fast, your body is having a physiological response, and you’re probably not processing information in a way that you would if you were in a calm setting where you knew you had to focus on something. Elizabeth Loftus, I think, was one of the first psychologists to take misidentification in terms of how your brain processes these situations. She did studies where she simulated accidents or crimes and saw how people on a psychological level process information. She’s very highly published. The moral of the story is that you aren’t processing information like you normally would and you’re probably not retaining information like you normally would. In a lot of eyewitness misidentification settings, it’s not that people want to misidentify an innocent person or to send an innocent person to jail; it’s that somewhere in their brain they have created this false idea that this innocent person is the person who committed the crime against them. Some of that can be from police and some can be from their own personal misunderstanding of the situation.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): I know there has been some controversy around different types of line-ups and identification procedures. Do you have any thoughts on, for example, how a show-up identification can create a lot of implicit bias compared to other types of lineups?

D.C. Public Defender: Yes. Show-up identifications are inherently suggestive. Certain Appellate Courts have recognized that. They recognized the inherent suggestivity. But courts and prosecutors still heavily rely on them.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): With the different ways that you can identify someone with law enforcement, whether that’s a line-up, show-up, a photo array, or sequential photos, do you have any thoughts on what is the most accurate way or what are some ways that create the most bias?

D.C. Public Defender: I don’t know if I have a good answer to that because I think if there is one take away that I hope people have about eyewitness misidentification is that we should be more skeptical of it, just as a general rule. I think the biggest thing we really need to look at is whether police departments have policies and procedures in place when conducting these identifications that account for bias and suggestivity to make it as neutral a process as possible. If they don’t have those policies, they should adopt them. If they do have those policies, we have to make sure they’re actually following them.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): Are there any measures you think that could reduce the risk of these misidentifications, for example policies like you were just saying, or examples of some sort of training that could be effective?

D.C. Public Defender: I think one thing that could be helpful that we don’t see often, at least in my experience, is having a neutral person conduct the identification procedure. A lot of times the people who are conducting the photo array, or the show-up, are the first responding officer or the assigned detective. It’s folks who have a vested interest, who know the most about the state of the investigation generally. This can introduce bias, consciously or subconsciously. Bringing in neutral people who don’t know the state of the investigation or who don’t know who the suspect is can remove some of that bias. I also think separately we always need to be sure that law enforcement is not leading the witness to make an identification, is not pressuring them to be more certain than they actually are, and if the person articulates an inability to identify, accepting that at face value.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): In terms of trials and criminal proceedings, how heavily do prosecutors, juries, or the court, rely on eyewitness testimony?

D.C. Public Defender: I think it’s safe to say that if there is an eyewitness identification in a case, the prosecutor is going to present it as evidence almost always. I think it was also Elizabeth Loftus that looked into this, but juries really do listen to it because I think jurors want to believe these complainants who a lot of times have no negative motive. It’s not like they have a reason to lie. The Innocence Project has also taken a look at this. But, juries want to believe eyewitnesses and do rely on it heavily when they end up convicting the person.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): From the public defender’s perspective, what are the challenges that come with that? If you’re trying to dispute the reliability of that testimony or anything like that?

D.C. Public Defender: I think you have to push back on the well-accepted idea that eyewitness identification is reliable and trustworthy. That is an idea that is ingrained in a lot of people. Having to counteract that deeply held belief can be tricky. It’s why in certain jurisdictions defense attorneys are allowed to put on expert testimony about the unreliability of eyewitness identification, especially when it comes to cross-racial identification. That’s one way public defenders are sort of combating it, by bringing in experts of their own. But I think the other thing is any time you’re cross examining a civilian witness who you think has misidentified your client, you constantly have to strike a balance between calling their testimony into question and not seeming like a bully or alienating the jury. I think that is maybe more of a strategic call that is made on a case by case basis, but it is something that we as public defenders have to actively consider when we’re dealing with the issue of misidentification.

Bruin Political Review (BPR): Is there anything that you wish people understood more about eyewitness misidentification or that you think should be more known?

D.C. Public Defender: I think I would just hope that people would be more skeptical of it across the board. My hope would be that no one would rely fully on an eyewitness identification in convicting someone, because there are so many issues that come along with it, such as the suggestivity of police involvement, potential implicit bias, or the Elizabeth Loftus effect of not really processing information quite the same when you go through a traumatic experience. My hope would be that people who one day are going to be on juries would have this understanding that they need to be skeptical of this.

Sources

[1] Innocence Project. “How Eyewitness Misidentification Can Send Innocent People to Prison.” April 15, 2020. https://innocenceproject.org/how-eyewitness-misidentification-can-send-innocent-people-to-prison/.

[2] Innocence Project. “How Eyewitness Misidentification Can Send Innocent People to Prison.”

[3] Carlson, Curt, et al. “The Weapon Focus Effect: Testing an Extension of the Unusualness Hypothesis,” Psychology Faculty Publications, Texas A&M University College of Arts and Sciences. 2016. https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/psyc_faculty/8.

[4] Innocence Project. “The Role of Race in Misidentification.” August 11, 2008. https://innocenceproject.org/the-role-of-race-in-misidentification/.

[5] Laura Connelly. “Cross-Racial Identifications: Solutions to the “They All Look Alike” Effect,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law. 2015. https://doi.org/10.36643/mjrl/vol21/iss1/5.

[6] Commonwealth of Kentucky Public Defenders Department of Public Advocacy. “Eyewitness Misidentification.” https://dpa.ky.gov/kentucky-department-of-public-advocacy/about-dpa/kip/causes/misid/.

[7] National Policing Institute. “Confidence, Latency, and Accuracy in Eyewitness Identifications Made from Show-Ups: Evidence from the Lab, the Field, and Current Law Enforcement Practices.” https://www.policinginstitute.org/projects/confidence-latency-and-accuracy-in-eyewitness-identifications-made-from-show-ups-evidence-from-the-lab-the-field-and-current-law-enforcement-practices/.

[8] National Institute of Justice. “Live Police Lineups: How Do They Work?” https://nij.ojp.gov/media/image/19686.

[9] IACP Law Enforcement Policy Center. “Model Policy: Eyewitness Identification.” September, 2016. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/EyewitnessIDPolicy2016.pdf.

[10] Commonwealth of Kentucky Public Defenders Department of Public Advocacy. “Eyewitness Misidentification.”

[11] Commonwealth of Kentucky Public Defenders Department of Public Advocacy. “Eyewitness Misidentification.”

[12] Brooks, Samantha, et al. “Psychological Impact of Being Wrongfully Accused of Criminal Offences: A Systematic Literature Review.” Medicine, Science, and the Law. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0025802420949069.

[13] Helen O’Neill, “The Perfect Witness.” Death Penalty Information Center. 2001. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/stories/the-perfect-witness.

[14] Commonwealth of Kentucky Public Defenders Department of Public Advocacy. “Eyewitness Misidentification.”

[15] Commonwealth of Kentucky Public Defenders Department of Public Advocacy. “Eyewitness Misidentification.”

[16] New Jersey Attorney General’s Office. “Attorney General Guidelines for Preparing and Conducting Out-of-Court Eyewitness Identifications.” February 9, 2021. https://www.nj.gov/oag/dcj/agguide/Photo-Lineup-ID-Guidelines.pdf.

[17] Bob Farb. “North Carolina Statutory Requirements Concerning How to Conduct Lineups and Show-Ups,” University of North Carolina School of Government Blog. June 12, 2017. https://nccriminallaw.sog.unc.edu/north-carolina-statutory-requirements-concerning-conduct-lineups-show-ups/.

[18] Colorado 74th General Assembly. “Measures to Expand Postconviction DNA Testing.” House Bill 23-1034. March 10, 2023. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb23-1034.