China’s Threat to American Hegemony: Is This It?

America’s hegemonic decline has been ongoing since the early 2000s, but the US is now facing an increasingly difficult path to maintain the liberal international order. The emergence of China as a military peer-competitor, preeminent economic power, and a regional player through the Doha Round and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) represents the most significant postwar challenge to American leadership, leading to the revitalization of a Cold War-like setup that is causing many countries to hedge their bets between the US and China.

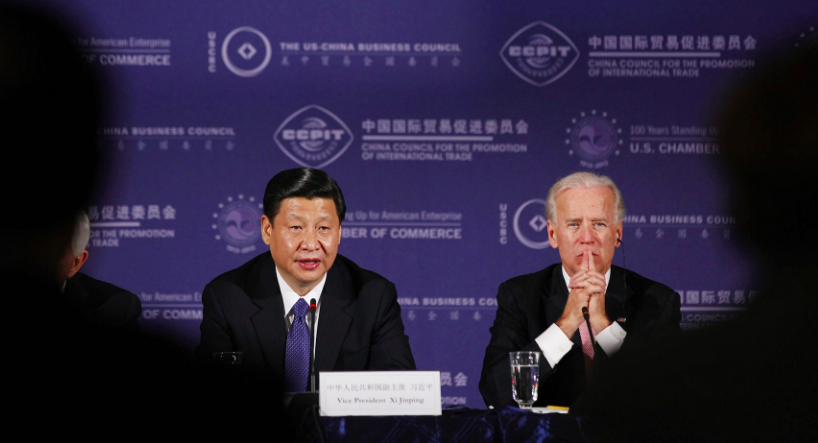

While President Biden’s recommitment to the Paris Agreement and the World Health Organization signals America’s willingness to re-engage in global affairs, Biden has to first address issues within its borders such as Covid-19, economic recovery, racial injustice, and the deepening political polarization before setting his eyes abroad. With the resurgence of nationalism and the increasing assertiveness of both China and Russia to balance against American foreign policy, this next few decades will be crucial in determining whether the US can continue to maintain its global presence and its role in a potentially bipolar or multipolar landscape.

When Donald Trump was elected president, he pledged to put “America First” and protect American jobs from being outsourced elsewhere. Yet, Trump’s nationalist rhetoric threatened to dismantle the very pillars of liberal internationalism. Within four years, Trump withdrew the US from various international agreements and organizations, even calling for the disbandment of NATO and the European Union.[1] Trump’s unwillingness to cooperate on multilateral forums alienated the US from the rest of the world, fracturing Washington’s relationship with its key allies and trading partners. He pandered to autocrats like Putin and Kim Jong Un, weakening the merits of placing liberal values such as democracy and human rights at the heart of foreign policy. Trump’s clear preference for zero-sum, transactional politics further supports the notion that the US is abandoning its commitment to promoting a liberal international order.

The increased isolationism from the US led to trade protectionism that culminated in a trade war against China. However, tariffs led to the loss for U.S. consumers of about $16.8 billion annually and a reduction in American jobs. On the other hand, China experienced an overall trade surplus of $78 billion and its exports to North America increased by almost 12%.[2] Trump’s trade war was never beneficial for the US in the first place, but his overt persistence in strengthening America had instead invited China to dominate the US in its own playing field.

Even after Trump left office, the US is facing an extenuating task of addressing the dangerous aftermath of nationalist movements. The insurrection at the Capitol by Trump supporters to overturn the 2020 election results shook the core of American democracy, eroding the “American exceptionalism” that champions US virtues of fair elections and smooth transitions of power around the world. The incident was a blow to American leadership; after all, if the US can’t practice these principles in its own land, how can it expect other autocratic countries to do the same?

Over the past year, the Covid-19 pandemic has further accelerated the erosion of American hegemony. Trump’s reluctance in acknowledging the consequential effects of Covid-19 helped to drive its politicization. Instead of a federal-led effort in tackling the virus, we witnessed disjointed state-by-state efforts based on political leanings to address the outbreak. While some states imposed some sort of lockdown, others never even issued a statewide mask mandate. Furthermore, Congress’ inability to agree on additional relief measures after passing the CARES Act last March poses a significant challenge for the US to stimulate its already weakened economy, making it more difficult for the US to exert its economic influence globally, the very foundations of American leadership.

Washington’s withdrawal from the WHO last year drew outcry from many parties, and although Biden recently rejoined the global health body, China filled the vacuum left behind by the US and pledged to play a coordinating role in multilateral forums to combat the spread of the virus. Throughout America’s absence, China portrayed itself as a benevolent donor of aid—providing emergency medical aid and loans to more than 130 countries and four international organizations.[3] Although many countries still resent Beijing’s initial failure to handle the outbreak, its successful fight against the virus and continuous aid to struggling countries helped to increase its influence in the health sector, jeopardizing Washington’s role in navigating the world through future global health crises.

When Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in his third day of office to “protect American interests,” the US lost a sizable opportunity to drive the trade playbook in the Asia Pacific. The free trade deal would have allowed the US to lead the way in global trade rules, bolster its leadership in Asia, and strengthen its alliances in the region. The TPP would also be an effective approach in limiting China’s distortion of international trade. While the rest of the TPP members proceeded to ratify a new deal called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), China’s exclusion from both of these deals propelled it to push for the ratification of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP),[4] the world’s largest free trade deal involving ASEAN, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

Although the RCEP is not as comprehensive as the CPTPP, the deal signals the region’s willingness to move ahead without the US towards a China-centric trade liberalization. It is a significant loss for the US because it now has even less leverage to pressure China into modifying its trading and economic practices to meet US standards. On top of that, Trump’s detachment from the TPP allowed many of its Asian members to start embracing China’s growing economic role in the region. With China already being one of their major trade partners, the RCEP will significantly increase China’s influence in the region.

In 1997, when Russia and China pledged to contest the liberal aspects of the US-led international order, the Western world downplayed and dismissed it as wishful rhetoric. How were Beijing and Moscow able to overcome decades of mistrust and rivalry to cooperate against U.S. efforts? Back then, it was a long shot. But today, China and Russia are working together on multiple fronts to contest the liberal aspects of the US-led international order, posing a significant risk to US hegemony. They created new international institutions and regional security organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization that directly challenges the traditional Western structures of global governance. More recently, China signed an agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), an economic union consisting of Russia and former-Soviet republics, to invest nearly $100 billion into the EEU through various BRI projects.[5] The agreement also opens up the Chinese markets for Russia to trade its oil and natural gas, which has suffered a $150 billion decrease in capital flow into the sector due to economic sanctions imposed by the EU and the US.[6]

Despite BRI’s inroad into Central Asia, which Moscow still considers as its backyard, Russia is vocally supporting the projects, defying predictions that both Beijing and Moscow would be unable to tolerate each other’s international projects. BRI projects such as the Moscow-Kazan High Speed Railway also utilizes Chinese technology and equipment for its construction, spurring rapid developments in a country which has lacked access to Western technologies for decades.[7] China has also proved willing to accommodate Russian sensitivities by abstaining to condemn Russia’s annexation of Crimea, even though doing so contravened China’s long-standing opposition to separatism and violations of territorial integrity.[8] Additionally, Trump’s trade war with China only gave Beijing additional incentives to support Russia’s economic development, since economically empowering Russia would mutually benefit both parties in achieving the common goal of toppling US dominance.

The unraveling of American hegemony is undeniable, but the US can still salvage its position by focusing on the one region experiencing a dynamic shift in hegemony—Asia Pacific. Washington’s top priority should be to rejoin the CPTPP, which would allow the US to re-engage and reassert its leadership in the region by countering China’s growing role in the region. The UK’s potential participation in the CPTPP should also serve to further encourage Biden to ratify the deal since there would now be an additional Western nation capable of fending off China’s influence in the region.[9] Most importantly, the US needs to be committed to amending Washington’s frayed ties with its Asian counterparts. Collectively, these Asian countries play a large role in balancing China’s expansion in the South China Sea. The sooner Washington strengthens these relationships, the sooner will it be able to plan a joint response with its allies should tensions with China escalate.

Washington’s race against China cannot be fought alone. Instead, Biden needs to revitalize the trans-Atlantic relationship after years of downright antagonism under Trump. Despite China’s rise, the US and the EU are still the pillars of an open and stable international system. Hence, it is pivotal for Biden to push for the adoption of a unified trans-Atlantic stance against China. Additionally, the EU’s recent announcement on the new trade deal with China should only serve as a wake-up call for Washington to step up its leadership role in the region.[10] Washington needs to renew its partnership with the EU to better address China’s increasing geopolitical threat in the region, and a united US-EU front could potentially spearhead a broader multilateral coalition of like-minded countries to maintain the international order and blunt Beijing’s efforts at the world stage.

Even with strong Asian and EU ties, Washington has to get used to an increasingly contested and complex international order. There is no simple fix for this. Even at the peak of the unipolar moment, Washington was not always able to secure the commitment of some countries to follow America’s visions of international order. Now, for the US to continue maintaining its hegemony abroad, it has to first get its own house in order. On the other hand, China will face significant obstacles in forming an alternate system. A reinvigorated US foreign policy is capable of exerting significant influence on the international order, but to succeed, Washington must first recognize that the world is no longer the 1990s. The unipolar moment has passed, and it isn’t coming back.

Sources

[1] Barnes, Julian E., and Helene Cooper. “Trump Discussed Pulling U.S. From NATO, Aides Say Amid New Concerns Over Russia.” The New York Times. The New York Times, January 15, 2019.

[2] Hancock, Tom, James Mayger, and Jeff Black. Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, n.d. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-11/how-china-won-trump-s-good-and-easy-to-win-trade-war.

[3] “China Says It Has Help over 130 Countries and Intl Organizations Fight COVID-19 Pandemic,” n.d. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-04-10/Chinese-experts-share-experiences-in-combating-COVID-19-PzeGMp0uHe/index.html.

[4] “ASEAN Hits Historic Milestone with Signing of RCEP - ASEAN: ONE VISION ONE IDENTITY ONE COMMUNITY.” ASEAN, November 15, 2020. https://asean.org/asean-hits-historic-milestone-signing-rcep/.

[5] Remyga, Oleg. “Linking the Eurasian Economic Union and China's Belt and Road.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 9, 2018. https://reconnectingasia.csis.org/analysis/entries/linking- eurasian-economic-union-and-chinas-belt-and-road/.

[6] Bimbetova, Bibigul et al. “The Impact of International Sanctions on National Economic Regime of Target States: The Case of Energy Sector (Oil, Gas and Renewable Energy).” Academy of Strategic Management Journal. Allied Business Academies, July 22, 2019. https://www.abacademies.org/ articles/the-impact-of-international-sanctions-on-national-economic-regime-of-target-states-the-case-of-energy-sector-oil-gas-and-renewable-8366.html.

[7] “Russian Revolution: Is the Moscow-Kazan High-Speed Rail Project on Track?” Railway Technology. n.d. https://www.railway-technology.com/features/moscow-kazan-high-speed-rail/.

[8] Wong, Sue-Lin. “China's Xi Vows Zero Tolerance for Separatist Movements.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, November 11, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-politics-sunyatsen-idUSKBN1360N4.

[9] “UK Joins ASEAN as Dialogue Partner, Looking at Joining CPTPP Asia-Pacific Free Trade Agreement.” ASEAN Business News, January 26, 2021. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/uk-joins-asean-as-dialogue-partner-looking-at-joining-cptpp-asia-pacific-free-trade-agreement/.

[10] Amaro, Silvia. “China's Investment Deal with the EU Has Raised 3 Big Concerns in Europe.” CNBC, January 6, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/06/china-eu-trade-deal-what-it-is-and-why-it-might-fail.html.